34. food processes

Some time after the Song Contest, we sat our finals exams. After those, we sat down to a finals dinner.

The Worcester language set. In a small private dining room in college, which looked a couple of hundred years old. Seven or eight of us, with our two tutors: Frank Lamport, a tall friendly man who taught german, so I never had classes with him, and Keith Gore. Exams were over (we didn't know our results yet) but we still had to wear gowns.

Someone at college, who was studying law I think, told me our language group was much closer than his lot; we got on with each other. And that was true. We weren't all close friends, but we had a laugh when we met up, and some of us shared places to live: me and Steve in Headington; Harry, Martin Neubert, and two others the top flat at Banbury Road. That lot were sweet when they thought I'd been kicked out of college, and some of us had a chinese together in our first year.

After college, I shared flats with Pat and Harry, and I'm still very much in touch with Pat, Steve, and Martin even though they live in Bristol, Paris, and Dormagen. Back in Oxford, I even cooked a meal for the whole set, and they were polite about that!

So this finals dinner was a convivial evening. I'm mentioning it for an incident, a very minor one, that showed another difference between the 70s and the decades that followed. Prepare for the attack of the avocado bombs.

*

Growing up in England in the Sixties was like living in a kind of endless postwar. Boys still wore grey shirts and socks to school, because they didn't show the dirt, so they didn't need changing so often and your parents didn't have to buy so many. No-one had a car. And food hadn't changed much even though rationing ended more than ten years before. You couldn't ration what wasn't there.

There were four fruits, no more. Apples, pears, oranges, bananas. Grapes in hospital, tangerines (called satsumas now) at christmas, when you also had nuts, which were too expensive the rest of the year. In 1977, when I started work as a advertising copywriter, they put me on new product development with the other newcomers - and told me not to invent chocolate bars with nuts, because they cost too much much.

Salads had tomatoes, round lettuce, and cucumber, nothing else (except the odd radish or spring onion if you were unlucky). My dad grew veg in the back garden, so Mum could give us different kinds of lettuce, though I still haven't forgiven them for the radicchio they planted, bitter as fuck. Full of iron apparently, but I'd rather eat a nail that's been in the ground.

But we did better than most for fruit.

One of my mates asked me how many different kinds we had in the garden.

Well, the fruit trees were already there when we moved in. Three short apple trees, eating and cooking. Two tall pear trees. Four kinds of plum, including greengages. Grapes in a greenhouse, though they never ripened in those days.

Meanwhile my dad planted strawberries, raspberries, gooseberries, blackcurrants (better in Ribena, which ruined our teeth), loganberries -

Oh shut up. How big's your garden, then?

Then they'd come round and see how much fitted into a long and quite wide garden. As I say, the three of us kids didn't have much of an area to play in, but the vegetable patches kept the old man occupied when he retired.

We were a rare family for food, because we were italian and had pasta. It was cheap then as now, so you ate great bowls of it.

We'd have our english schoolfriends round for tea, and we always asked Mum to serve them spaghetti first time, because it was the hardest to eat! They were worried about looking awkward and making a mess, and we'd watch them twirl their forks round and round so the spaghetti strings wouldn't dangle too far, then take pity on them by showing them it was alright to bite those bits off. After we'd had our fun, we let them try rigatoni and conciglie. Not farfalle, because they can't cook evenly. Only non-italians eat farfalle.

Being a kid, you'd be tempted to stuff too big a ball of spaghetti in your mouth, then it would go down the wrong way and burn your throat. Worth it for Mum's bolognese sauce.

Dad didn't care about fresh pasta. It had been too expensive for his family back in Italy, and you couldn't find it in Reading anyway. He kept different kinds of dried pasta in those long jars you found in sweetshops, with the black screwtop lids. I've kept two of them to this day, only the pasta's wholewheat now.

Mum put together a great bolognese. She made pizza as well, though I never got used to the anchovies. I couldn't understand why anyone would want to eat those things.

My aunt Maria, one of dad's sisters, came over from Genoa once, with cans of anchovies in oil. She decanted them into a big bowl, then sat with Dad and ate the lot with crusty bread. I had two, which was one too many. Jesus, all that salt.

Mum's apple pie was as good as her pastas, though I was an ungrateful little git about that too! The pieces of apple were too big for my liking, they burned the top of your mouth and I preferred those small shop-bought pies filled with sugary gunk and tiny pieces of apple: delicious, especially as you didn't get to eat many because they were more expensive than the penny chews which wrecked our teeth.

Mum baked bananas in the oven, heady and delicious, adding a dash of lemon juice, and served brittle pastries in the shape of bow ties, dusted with soft sugar, another italian way of making something tasty out of very basic ingredients. Mum called them crostoli, though they've got various other names in italian: tufts, rags, gloves, little butterflies, chatters, lies (yes, really) - and fritters, but Mum made other things with that name, the same one in english.

The crostoli were deep fried, like her fritters, which were legendary. Apple and especially banana again - though she must've run out of housekeeping money one day because we came home from school to find eel fritters on the table. Worse than the pig's head we found on top of the fridge one day: we knew we weren't going to be eating it like that.

Batter can't disguise slices of fucking eel. Mum knew that was a step too far (I think we actually cried!), so she threw them away and made paste sandwiches. That's how short of money most working people were. Whitebait was fun to eat but poor man's nosh at the time, and we even had to eat tripe and pig's trotters sometimes, and the dreaded polenta (how did that ever get into restaurants?) - though pan-fried brain was delicious.

My dad wasn't idle either. His lasagne, gnocchi, and pesto were the best ever made.

The lasagne were dry, like slicing through the strata in a rock formation, not wet and lumpen like the english make them. The gnocchi were heavy and sticky, unlike the suppositories you buy in supermarkets. And the pesto was a green gloop. When I met someone who made some that came out like that, I wanted to marry her, but she was a friend of my fiancée!

One thing most of our english pals didn't have to endure was bread and milk. Cereals were too expensive in our early days, so we sat through bowls of white sliced floating in warm milk with sugar. The crusts were bearable, but not the soggy pap, which made me gag sometimes.

Just to show how you turn blasé when you get used to things. Cornflakes were a luxury for a while, but when we had them regularly they became boring (though they tasted better, completely different, without milk). They were the last two packets you'd pick in a six-pack called Variety, which had Frosties and Rice Krispies. A family pack of Coco Pops was the grail, but even something tasteless like Special K was better than milk and bread, which were made to be consumed separately.

*

If meat paste wasn't a wartime staple, it fucking well should've been. And it should've lost the war.

It came in thin little pots the shape of a conga drum, with ridged sides and a metal lid. You kept the pots to put powder paint in. The paste itself was more grey than brown and tasted like - well, paste. Nothing compares with it.

When I worked in advertising, one of my bosses referred to dogfood as crushed beaks, because any part of the animal that was unfit for human consumption was ground up and made into Pal and Chum (our labrador got Chappie, the cheapest). Same with meat paste. We couldn't afford Shippams or Princes, so it was some make I can't remember.

What makes me smile is they pretended it came in different flavours. Ham and tongue, ham and beef, beef and chicken. They may have had different ingredients, but the taste was exactly the same. A crushed bone is a crushed bone. Fish paste was worse. It smelt like catfood.

Me and Mick used to eat Bonio occasionally. For fun, not out of poverty. The bone-shaped biscuits we gave to our dog. They tasted better than fish spread, though one was more than enough.

I'd nick a whole packet of jelly cubes from the cupboard and eat them all in one go. The first two were delicious, the last two made you feel sick. Pineapple was best.

Yes, we had spam too. But like the branded pastes, we didn't spend money on Spam itself. Instead industrial-size tins Dad got from work, the wonderfully named 'pork luncheon meat'. Luncheon! It was mainly fat and blood, therefore pink.

Don't believe what people say. There's no nostalgia in spam. The internet version got the name for a reason. Spam fritters were dreadful, like slimy salty turds. Here we were, being called greasy dagoes while the english ate bread and dripping, which is lard warmed up. Continental breakfasts were milky coffee with a pastry, not british death platters. A Mediterranean diet can save your life.

But spam, sliced very thinly and eaten cold, that was alright in sandwiches with salad cream, another euphemism from the advertising people. When my mum made mayonnaise - a real skill to get right, let me tell you - I wasn't keen because it didn't have the vinegary zing of salad cream. When sandwich spread appeared, it was a real luxury. All those bits.

Like everything else, you got used to salad cream and even preferred it. I've eaten every kind of mushroom, and the cheap button ones are the best. Jersey toms are the best tomatoes. The best vinegar is sarsons malt. But I can live without the piccalilli that used to be so popular.

Crisps were made by Smith's and came with a tiny blue bag of salt which was hard to open, so you used your teeth and got all the salt at once, not a good thing. I associated them with pork pies and oranges on coach trips with the mental patients. Ready salted were a big improvement, and when salt & vinegar came in, and chese & onion, we were in heaven.

Bread was white, of course, and sliced. Whitened by bleach. Brown bread was white bread stained with tea. Wholemeal and granary were unheard of.

When I was seven, my primary school teacher had a soft spot for me. Miss Hart had no kids of her own. She took me on the ferry to France for the day (banana sandwiches: whatever happened to them?).

I would've banned packaged bread decades ago, but it's cheaper and a lot of people still need that. Pumped with air to make it go further. If you can't knock someone senseless with a loaf, don't buy it.

Ice cream was that white stuff from a machine in vans. Italians would've called it something else. It came with a flake if you had any extra money, which we never did. They called it a 99, and that bit of flake was like the extra slice of cheese to Elvis. When he was young, he was so poor he couldn't afford a cheeseburger. When he was rich, he overdosed on them.. I never liked flakes that much, but they made a difference to that ersatz shaving cream from the van.

The ice cream you ate at home was by Wall's. It was always vanilla and made with 'non-milk fat', presumably the same thing that went into their sausages. For special occasions: Wall's Neapolitan - vanilla, chocolate, so-called strawberry - which was about as native to Naples as spam.

I got a taste for Wall's sausages (the posh ones had too much proper meat), but not their ice cream. We had the real thing on holidays in Italy.

Over there, we found grissini as well. I didn't know there was an english word - breadsticks - because you never saw any in Britain. Panettone too, which was wonderful, especially when you warmed it up - and if you were lucky, you came home with torta dura, hard cake, made from almonds, or torta paradiso, made with potato flour, which melted to dust in your mouth, both of them sweet and delicious. Nutella, unheard-of in Reading, was a fantastic find, including the stripy version. Asti Spumante then Lambrusco were a kid's intro to wine.

At the time, italians didn't trust their tap water. San Pellegrino instead, the nearest thing we had to coke. As a kid, I wanted to believe mineral water came out of the ground fizzy, carbonated by an interaction with subterranean rocks. Still do.

*

It wasn't all crap nosh - especially if you were foreign.

Not just the pasta and Mum's cooking. Now and then, a van would come round.

When people emigrate, what they miss most is the food. Baked beans and marmite in the south of France. Wall's sausages. There must've been a couple of thousand italians in Reading, living on white bread and paste and processed cheese. So someone saw a gap in the market.

In those days before multiple supermarkets and cars, a small van would appear. Olive oil and lambrusco and spaghetti that wasn't cut up in tins. Buffalo mozzarella and marsala and mortadella with slices of pistacchio in it and panettone at easter. Just the smell of the van when they opened the back door. English food shops have never smelt of anything.

Those vans didn't turn up very often, but there were one or two places in Reading town centre.

Even a coffee shop, a shop for coffee and not much more than coffee. Cottle's, in the arcade by Marks & Spencer. I'd go in there for my dad. Half a pound of colombian, half a pound of kenyan mountain, mixed together in beans. They'd grind it for you, though he preferred doing that at home.

But coffee was for him. Apart from a dribble in hot milk, I never touched it and hardly ever drink it now. A better shop for the whole family was the swiss deli on King's Road. Il tedesco, my dad called it, the german.

Different kinds of salami and cheese, biscuits that weren't digestives or bourbons, jars of olives, black cherry jam, which we'd never seen anywhere else and was the most delicious thing I've ever eaten. You don't need me to list what's in a delicatessen - but you would have at the time. They were very rare back then.

When we were kids, they'd give us sweets on the way out. Long thin things from abroad, with a liquid fruit filling and wrappers with triangular ends. Sweets doubled as loose change in Italy, where there was always a shortage of low-denomination coins.

Friendly people in the swiss deli, and I can still picture them now. Two older men, one with glasses, a woman, and a younger guy. Always smiling. Striped aprons.

Parmesan, like olive oil, was really expensive. We didn't have olive oil much. But parmesan is italian cocaine, the only animal product I didn't give up when I turned vegan. In the 60s and 70s, it was so precious you got only a light dusting on your bolognese - but that was better. When I started work and could afford lumps of the stuff, I'd heap it on my pasta - but it tasted better when there was less of it. I hardly use it now.

Same with peanut butter. Again, hard to believe how rare this used to be.

*

We'd only just moved into the new house in Caversham when a four-year-old boy stuck his head round the low brick post at the entrance to our front garden. He went on to be best man at my brother's wedding.

The boy had three sisters and canadian parents. When we went round for tea, they gave us sandwiches (white sliced, of course) with this amazing substance called peanut butter, which we'd never heard of. I mean, peanuts yes. But butter from peanuts? As good as cherry jam.

It was imported, so it cost a lot, which meant all you got was a smear across your butter or margarine. But again that was better than the years to come, when you could have as much as you wanted. Kids shouldn't do without, but a little scarcity - a little - makes things taste better. You just appreciate stuff more.

*

Same when you can't afford to eat out.

Even in the 1970s, working people didn't go to restaurants much. Anyway, as an italian family in England, we didn't use italian eateries. I didn't know any in Reading, and the food was better at home.

For a treat, we'd be taken to the European Grill in Caversham. Milky coffee in glass cups. We never had brown sugar cubes at home, so my brother would fill his pockets. We had snacks there, not full meals, but glamorous all the same. Took the girlfriend there when I was at college, and the steak diane was good, though I couldn't help mentioning the price. A whole two quid, quite a leap from 50p pizzas.

As kids, we tried a chinese once, with my mum, a restaurant above the Co-op - and I liked absolutely everything, especially the lychees, which we'd never heard of, and the chicken and sweetcorn soup with its strips of egg and monosodium gloopiness. See takeaway spring rolls below.

But I didn't have my first curry till 1971, when I was sixteen. It was in Oxford.

The Shawshank boarding school I was sent to, it had a couple of teachers who were decent people. One of them, Ron Lyle, I met up with several times after I left. He’d fought at El Alamein, military moustache, and went to Worcester College like I did. One day we're standing in front of the war memorials there, and he's talking me through some of the names. Unique to look at a roll of the dead with someone who's fought alongside them.

He made me look at something else differently too. In my day, he said, when we danced we touched each other.

A happily married man, Mr Lyle. Kids and a bungalow in the countryside. I went to his funeral at the local church.

He was the french teacher and I was his prize pupil (at A Level, I was his only pupil!). One evening he takes me to London for a lecture on Molière (who reappeared during Oxford finals). We go by train and have a bevvy in the station bar. Ron asks what I want to drink, and I say whisky and coke, which shocks him a bit. He was expecting me to ask for half a pint same as him, but beer was bitter pisswater in those days.

After the lecture, we get back to Oxford, and the school budget runs to a meal for two at an indian restaurant. Either that or Ron paid for it himself, which was typically kind of him. The Standard was on Walton Street, just up from Worcester College. It had the classic flock wallpaper, which was exotic to a teenager, the lighting was nice and low, and all the food looked brown, a good colour to eat. I had something with shrimps, and everything was spicy, other-worldly, and delicious. We simply didn't eat things like this.

I remember smiling when the waiter asked if we wanted 'any poppadum'. I didn't know what they were and it was a funny word. A really great occasion.

I mention it because the 70s were when curry houses took off in England. When I went back to Oxford as a student, there were four in Walton Street alone, within two hundred yards. The Standard, the Dildunia, the famous Uddin's, and one whose name none of us can remember (presumably the Bombay). When Uddin's adverts appeared at the cinema, people clapped and chanted.

Not just indian. After decades of postwar austerity, we were being introduced to all kinds of different food.

*

Some needed some getting used to.

There was a spare room in our house, and we took in lodgers for the extra money. One day a stocky young mexican appears at the door, a gum-chewing trainee priest. Mexicans have a tradition for high diving, and Carlos Martínez was the first person I ever saw do a swallow dive at the local pool, really impressive to a kid who couldn't swim.

He'd brought a couple of tins in his suitcase, knowing he couldn't buy green chillis in Reading. He'd eat four of them between slices of white bread. I licked one and had to put my mouth under the tap. Why would people do this to themselves? My mum joked that his taste buds had been burned away, but he was happy.

*

Tell someone you're going for a chinese takeaway, and you'll get no reaction at all. It's just a chinese. But in the Seventies, they were a bit of an event.

The first one I ever went to was also on Walton Street. Their spring rolls were the best I've ever had. They were called pancake rolls at the time, which gave you more info. They had a soft white inner lining, which I've never seen since, like a thin chinese-dumpling membrane under the crispy exterior - and they were drained to perfection, never remotely soggy or greasy. The beansprouts and tiny cubes of meat: utterly delicious. And they were the size of a mars bar, not the little fingers you get now. A 1970s mars bar.

These rolls cost 14p each, and I started eating two at a time. On my 19th birthday, I ordered ten! Ate eight in one sitting, on my own (I did have a girlfriend, but ten pancake rolls: aaah), then had the other two cold the next day. I know I'll never find any that good again.

*

Meanwhile a more major change you noticed in that decade was the rise of supermarkets and the demise of corner shops.

There was already a Sainsbury's in Reading, but for a while the small shops survived and some did well. Early on, apparently some people stayed away from supermarkets because they made customers do the work!

There seemed to be a shop on every corner. Usually sweetshops run by retired couples, just a converted front room. I can picture four in the space of a hundred yards near us. One of them went on till it was selling nothing but rich tea biscuits (another misnomer!).These little places were prime venues for minor shoplifting.

Two of you would go in. You'd ask for sweets from the big bottles on the shelves behind the counter, which took time to get down. While the old shopkeeper's got his or her back turned, your mate would dive into the fridge for a lolly or that crown jewel a cornetto.

But this exploitation of the old by the very young didn't happen all that much. You had to have cash to go in those shops in the first place, and we usually didn't. Pocket money wasn't a given.

Meanwhile off-licences were small dark places smelling of yeast. As a kid, you went in them only to return glass bottles for the few pence you got back. A financial incentive to recycle.

These shops weren't always on corners.

Gosbrook Road had a barber's next door to a cobbler, again just the front room with a bay window. I used to use both of them. The barber, who cut patients' hair at the mental hospital, gave me and my brother such a severe back-and-sides my mum stormed round to complain. Not much he could do about it then, but a warning for next time. She was a formidable mamma.

A shop on my street in Shepherd's Bush, which was probably once a pub, survived into the Nineties - I once bought just a packet of All-Bran and some toilet rolls! - but those Caversham stores disappeared years before that.

One of them, though, near our old house, is still there. Corner of Gosbrook Road and Washington Road which led to our street. But it became just another convenience store many years ago. Before that, into the 70s, it was like a mini supermarket, always full of local people and kids.

It was run by Mr Watts - DH Watts, Douglas - who was what you wanted a grocer to look like. In his forties, hefty, balding, pink-cheeked, genuinely jolly. His friendly blonde wife Hilde was german (Hildegard Radtke), so the place was something of a delicatessen. They seemed to really like people, knew everyone by name, and sold every foodstuff you could need. He even sliced his own ham, on that scary machine, a major thing for italians.

Ham was something I always hated in England. Half an inch thick, on white bread with too much butter. Disgusting. They did things differently on the continent. No-one could afford plane travel, so our summer holidays started with 24 hours on a train from Reading to Venice. When it stopped at a main station, a trolley would come past and you'd reach down to pay for soft rolls with just the right texture of crust, filled with cooked ham or prosciutto crudo or salami, sliced see-through thin, no butter. Watts's was an oasis for that.

With the ham sandwich at the station, a bottle of orangina. Again, you never saw those over here. Bits of real orange and no chemical aftertaste. Unforgettable even now

I've just read that the Wattses ran their shop from 1963 to 1986, but trade must've fallen away a bit during the late 70s. People were using supermarkets more.

Watts used to shut at 5.30. In their peak years, they didn't need to go beyond that because housewives could come out any time of day. When more women started working, shops had to stay open longer into the evening, and that's when the asians moved in. They worked really long hours. We were amazed we could buy things at nine o'clock. They turned into convenience stores because of the supermarkets, and they're all pretty similar now, across London too. Not proper food shops any more. Hilde Watts was with us until 2017, so she had a long life.

On the opposite corner of Gosbrook and Washington, the big barber shop stayed open for years (Mike Robinson?), though I used it only once and didn't see many people in there. Maybe it had a fixed rent.

*

High streets too, not just grocers on corners.

Even on the main drag in quite a big town, most of the shops were independent. Butchers and fishmongers, newsagents, florists, hardware stores, haberdashers, carpet shops. A lot of family businesses.

You had the odd supermarket, or a department store in towns the size of Reading and Oxford. There was a Timothy Whites before Boots took them over, and a Wimpy. But no Costa on every fucking street. In London, Soho had a lot of small italian restaurants and caffs, like the Centrale in the Pogues song. The Lorelei may have been the last.

Chain stores had probably started taking over in the 70s, but that seemed to accelerate afterwards.

In 1996, three of us went birding in Staffordshire. We stopped for a break in Leek. And saw the decline of the high street close up.

It seemed to be mostly one-off shops, including a caff that looked a nice place. But this was a sunday, and the entire town centre was shut. For tea and cake, we had to use the Sainsbury's on the edge of town, lying there like mistletoe, sucking life out of a town. It was packed, which said it all. Even worse nowadays.

*

I'm no social historian, but it seems to me that until deep into the Seventies, what with bigger families and low wages, working people couldn't afford to over-eat. Poverty's always been a major reason for people being smaller. Like my dad and cousins in wartime Italy.

In 1970, the average british man had size eight feet. Forty years later, it was ten. Women went up from four to six. And feet splay out with extra weight. For a long time now, people have been eating a lot more.

Ask anyone of my age and class if they had second helpings as kids, and I guarantee they'll say no. Your parents gave you exactly what they thought you should eat, or they could afford, and you didn't think of asking for more. And you didn't always get pudding (we didn't call it dessert: that was for posh people). Maybe that's why I ate so much gypsy tart at school.

One of my friends, from a large family, sometimes had only broken biscuits for dinner. There wasn't much spare cash for snacking, and a penny chew was just sugar, so it fucked your teeth but didn't make you fat. Crumpets were a treat, imagine that. So was corn on the cob. In Italy they used it to feed chickens.

Fat people were rare. Remarkable, to be remarked upon. I can't remember more than one or two at school or college, and no-one used the word obese.

Contrast that with early 2021, when a quarter of eleven-year-olds in Britain were clinically obese, with another 14% overweight. Type 2 diabetes is on the rise among kids, mainly because of increasing poverty (chicken nuggets and chips are cheaper than vegetables).

That was utterly unthinkable when I was a kid or a student. The same 2021 survey revealed that 75% of adults between 45 and 74 were obese or overweight. Three fucking quarters. There were diabetics in 1976, but we never knew any.

Doesn't necessarily mean people's health was better. Not when you're eating bread 'n dripping and smoking fifty a day. Again, ask people of my generation if they remember any eighty-year-olds and they'll have to stop and think. When my mum died at 40, I consoled myself that at least she reached middle age. Cue bitter laugh.

For her funeral, her catholic church in Italy brought out a little card. 'To you who loved life so much, the lord wanted to give days without end.' Imagine that. The unashamed heartless fuckers, twisting things that way. No wonder I stopped believing before I left primary school.

I sometimes imagine what her life would've been like, her being so full of it, if she hadn't been granted an everlasting one.

Meanwhile life expectancy in Britain was simply a lot lower. At the start of the Seventies, it almost touched 72 - but that's because the figure for women was over 75. The average for men was under 69. The government expected to pay you a state pension for only four years.

Not surprising when just about everybody smoked. And because they all did, you never smelled it anywhere, odd but true. Took my dad 45 years to die from it.

With less smoking, plus improvements in medicine and health awareness, life expectancy's up by more than ten years since then, an amazing statistic to me - though a lot of fat people live longer in a bad state of health, and the expectancy itself started to fall after Austerity in 2010.

No-one used gyms when I was at college. That really started under Thatcher. And I never saw anyone else when I went running as a teenager - though that's partly because I ran at night. People thought joggers were weird, and you're self-conscious at sixteen.

But maybe as kids we were generally a bit fitter. Most people didn't smoke seriously till they left school - and we did all that walking everywhere. I don't want to make it sound like we were all athletes, with legs like young antelopes, but we burned off the low-energy food we were eating. Middle-class kids probably ate better, but I can't speak for them.

*

Follow me while I jump ahead in time for a moment. Not just to the present day but the future of food. It messes with the chronology, but I can't find another place to put it. And I can't be persuaded to leave it out.

I watch the odd cookery competition on TV. And I wonder if this is the way we're always going to present food.

It probably is. Because it has been for thousands of years. Stretching your meat and tomato allowance by mincing them into a sauce. Using herbs. Discovering preservatives: oil, vinegar, salt, sugar, alcohol.

But it seems to have gone to extremes.

I don't mean fads that go on too long. Thank christ cranberries have disappeared, but who will rid me of that scourge of all vegans, butternut fucking squash, and the crime against nature that is sourdough toast?

No, I mean offal porridge and aerated beetroot. 'The best restaurant in the world' serving a duck's brain inside its own skull. Edible pine cones. Something's pancreas fried in reindeer moss, whatever that is. Strawberries and tomatoes cured together in koji. Tuna tartare rolled in cucumber skin, with 'a suggestion of toasted rice'. Anything with nasturtiums and monk's beard.

It's easy to make a list like this and take the piss out of it. But it shows how things have been going. And it's impossible to believe there'll be a worldwide movement and we'll only ever eat plain food again. But you can use your imagination.

Picture us looking back at a time when chefs used to paint their plates with a sauce, instead of putting it on the food so you could actually eat it. Remember how people used to insult the poor by paying thousands to eat meat in gold leaf or peeling their fucking broad beans. A restaurant that served you seafood, then gave you headphones so you could hear the sea (true story). One chef wanted you to lick his bricks, another one to suck citrus foam out of a plaster cast of his mouth (again, I'm not making this up). What the fuck is a pre-dessert?

Maybe one day we'll reject all that, like electric guitars kept making comebacks after prog rock and synth. Go back to putting nothing on a steak because you can't improve a good cut of meat or fish.

Places that did that, they existed in my time, though not many. There used to be an english restaurant in Kensington.

You don't hear that very often. A restaurant specialising in english food. I've no idea when Britain last celebrated its own cuisine as much as other countries. Too busy welcoming everything that comes in from outside. Good, but there's room for both.

Compare and contrast somewhere like France - and Italy, where my family come from. They're all in the north. One of my cousins and his wife used to take gastronomic tours of Puglia and Calabria - and never ate the same thing twice.

That's why we don't try much foreign food, he said. We're spoiled. Our regional cuisine is so good. Same in England, I said. Except we don't hear about it.

The Kensington eatery was in Holland Street. It was called the Holland Street Restaurant. Name as plain as its food - which was delicious.

Game pie, steak 'n ale, hotpots. Cabbage and mash. If I'm making it sound like someone's kitchen up north: it wasn't. Proper posh nosh, Dover sole and Whitstable oysters, with prices to match. Went there a couple of times with the Blonde. It was right alongside Ken High Street, but in a sidestreet, so I guess it didn’t get the passing trade. Real shame it closed down.

There weren't many places like that, and I'm not suggesting they'll ever be in the majority. But, you know, you never know. Absolutely nothing is certain...

I hear the 19th Century didn't rate Mozart.

Yeh, they thought he was just a tunesmith. El Greco was forgotten for centuries.

And get this. You'll never believe it. People used to think the Beatles were good.

Now you're just being ridiculous.

*

Right, end of detour. Back to the 70s.

In the middle of that decade, some things changed. Food improved.

We ate in restaurants more. Candles in bottles, layers of red and white wax dripping halfway down like cooled lava - and good pizzas.

Better ice cream appeared. Out of nowhere, a Dayvilles on Oxford High Street.

Before that, we had Wall's (above), 99s from ice cream vans, basic choc ices at the cinema, and the odd oasis like a shop in Caversham which sold orange sorbets and tutti frutti (vanilla cones with tiny cubes of dried fruit). Me and my best mate Mick Carter could never afford enough of those.

Now suddenly here's a place in Oxford offering 32 flavours. There must've been students who tried every one, though it wasn't a cheap place so I didn't go very often.

But the ice creams were good. Not exactly homemade but a cut above what we were used to in England. Even someone like me, raised on the real thing in Italy, gave it my nod.

*

Burgers were improving too. When you're used to a regular Wimpy, a Big Mac comes as a hefty shock, though maybe you miss the proper onions. Infinitely better was Brett's Burgers in Reading, near Greyfriars Church.

But I'm not talking about that. I didn't know McDonald's existed before I moved to London. No, I mean proper sit-down restaurants. Starting in Oxford.

Cassidy's was an american eatery on Little Clarendon Street. I was taken there by a rich italian a couple of years older than me who used to spend summer terms at my boarding school (along with the son of a president of Italy), then I went back after that.

This was a complete eye-opener. A real restaurant, and their burgers were like nothing we'd tried before. Thick patties of minced beef, cooked the way you wanted them, melt in the mouth, with decent chips - though what I remember most is the sauces.

Two in particular, both sweet. Something green and tangy, and one made with sweetcorn. You found them in the Tootsie's chain in London but not for decades since, gone like the red coconut dip in curry houses. Sigh.

Cassidy's happened to have a good-looking waitress with very long red hair (the stuff of Rick Bowden's fantasies!), but I didnt go there to look at her. Still can't believe those sauces disappeared.

*

You wouldn't catch Bernie Cook in a place like that. They didn't really cater for vegetarians. Indian restaurants did, but he didn't fancy those, so his choice was limited.

Even veggies with broader tastes struggled in restaurants. They didn't need to be catered for because they were uncommon - and didn't become common for years. Meanwhile vegans didn't exist. They were still on the planet Vega.

In the early 80s, I thought of making the change. Instead I kept on eating meat till 1990.

The moment I knew my heart wasn't in it was dinner one night in a restaurant, where the vegetarian choice was cheese platter. I eventually turned vegan in 1996. My turn to be part of a minority.

Even then, vegans were so rare people thought they could criticise you to your face. You were part of a freak show, so they could openly point a finger.

A lot of meat eaters got very defensive when you mentioned it, even though I was never evangelical in the slightest. Instead of attempting moral justifications for the inhumane slaughter of cattle and suffocation of billions of fish, they invariably brought up the nutritional angle. Most of the carnivores were amazed I could stand upright, let alone jog and use a gym three times a week.

At one party, I met a married couple. When they found out I didn't eat meat, they gave me a lecture on the Vitamin B Problem. How vegans had to take supplements, pills made from animal products.

This was news to me. I'd read about Vitamin B1 in wholemeal bread, brown pasta and rice, sunflower seeds, sesame seeds, brazil nuts and hazelnuts, peas beans and lentils, and corn on the cob. Vitamin B2 turns up in mushrooms, avocado, wild rice, mangetout, and muesli with soya milk. B3: same. Bananas have B6 and B12.

They used to fortify breakfast cereals when I was a kid. Probably still do. We didn't know thiamin, niacin, and riboflavin were B vitamins, but we never forgot the names. There was a rhythm to them.

But no, silly me, apparently I couldn't survive without tablets made from things someone had killed. Maybe that couple meant well, though they seemed eager to educate more than anything. They were my mate's guests and it was a party, so I kept shtum for once. What I wanted to say was thanks for caring so much. For imparting knowledge to a poor wretch like me. Because I'm obviously too fucking stupid to have done my own research.

Another time, another party, this one organised by the Royal Mail for its contributors (I used to write quite a lot for their stamps department).

I'm standing around with a couple of women and the husband of one of them, a big old slob in glasses. I never used to announce my dietary decision, but when I turned down the canapés yet again, one of the women asked if I was a vegetarian. Vegan, I said. Whereupon the husband gets stuck in.

He starts by saying he ate meat because our ancestors did and we should honour them. Well it was an original excuse. Then he says he's been to Africa recently and tucked into a thomson's gazelle!

I asked why he was telling me all this, and he said a friend of his knew a vegan sect in Nepal, and they were the worst people he'd ever known. What the fuck this had to do with me...

But again I proved I can restrain myself in this sort of gathering.

Mate, I said placidly. You're the rudest man I've ever met. Sort yourself out. Ladies.

And I graciously took my leave.

I kept bumping into our host. Hey, who's that opinionated cunt with the specs? You could express yourself freely in front of Philip Parker.

Oh, ignore the tosser. He's always like that.

There's less of that shit nowadays. Vegans abound. You might even suggest we're cool, if we weren't too right-on to say so.

Last time I looked, there were three million and counting, though I can't think how you arrive at a figure for that. Restaurants and food manufacturers advertise vegan options loudly (they even skipped the vegetarian option), and butchers shops closed down. Long way to go, especially with dozens of poultry factories polluting the River Wye - but reasons to be cheerful.

Except.

There's a tiny part of the back of my mind, the area marked churlish, that wishes I were still one of the very few, not a growing movement.

I don't mean this at all (more vegans means fewer animals slaughtered cruelly). But when we were rarer we were a gang, a punk band, us against the world. Now I'm unremarkable!

Same thing happens in other areas. I was in a pub in the mid-80s, when Born in the USA had just come out, and two of the guys in the group were moaning about the whole world climbing on the Springsteen bandwagon. They'd grown up with him when he was still skinny and bearded in a woolly hat. Now it was all muscles and power chords and mass appeal. You can imagine feeling like they did, but it's only Springsteen so get over it.

*

Back in my omnivorous days, being an italian family meant we ate calamari from time to time, but it was never in batter or breadcrumbs and therefore rubbery and tasteless and a bastard to swallow. Not what I called proper seafood. Until crustaceans started appearing on sheets of iceberg lettuce.

*

People take the piss out of the classic '70s dinner. For the life of me, I can't see why.

Prawn cocktail, sirloin steak, black forest gateau. What the fuck's not to like?

Big fat prawns in a mayonnaisy sauce. A steak, for christsake, fillet if you're lucky. With bearnaise and good chips. Washed down with a classy liebfraumilch. A cake with chocolate, cream, cherries, and kirsch. I'm kidding about the liebfraumilch.

My first meal like that was at the Mitre, on Oxford's High Street, a 17th Century building with a big gilded bishop's hat over the first-floor window. I was still at the boarding school when my mum took me there for dinner. Her boyfriend was venezuelan. He wasn't there that night, but the meal was paid for by his country's ambassador to Britain, who was a nice guy.

The Mitre was already a Berni Inn by then. It was the first place I had a steak, with french mustard and onion rings, both magical - and we sat in booths, partitions, which I've loved ever since.

Alright, this was special-occasion fare. But working people had a bit of disposable income by now (a phrase no-one used in the 60s because there wasn't any), and there were extra foods to try.

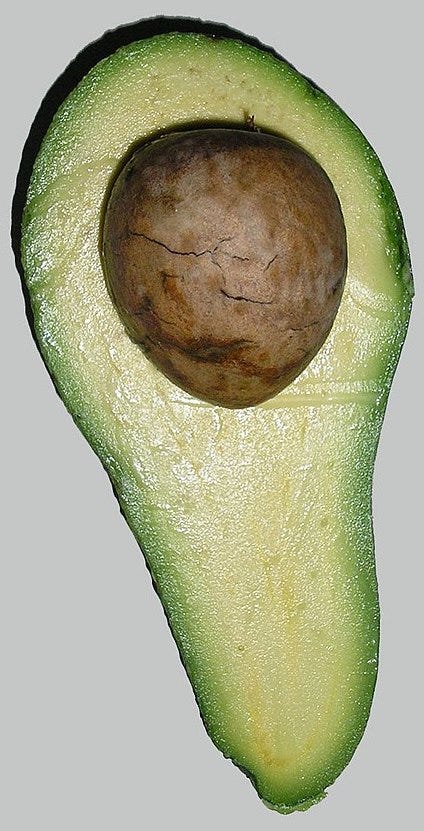

Including things we didn't know what to make of, like a chunky green thing that didn't taste of much. Because of its shape, they called it an avocado pear, though I couldn't imagine it in a fruit salad.

*

The finals dinner, then. At last.

I remember two things we ate. The starter and the dessert. I kickstarted the starter.

I can't remember trying an avocado before. Didn't think much of it, despite a vinaigrette in the hollow.

But even a tyro like me would've kept the thing on the plate if people had known what they were doing. Not me, the chefs.

Nowadays no-one would dream of serving an avocado rock-hard. I needed a chisel for mine. Instead I had a valiant stab with fork and spoon, only to send it skidding across the table. I can still see the oily mark on that polished wood surface.

Naturally everyone has a chortle. Keith makes a typically acerbic remark, but he's smiling and so am I. Can't remember if I managed to excavate enough avocado to eat, but it was a memorable moment -

Soon followed by another one. I hear a thud.

One of the dons has the same issue as me, only this time the avocado makes a longer dash for freedom, aquaplaning across the table before dive-bombing the floor. I'm pretty sure it was Keith! Chortling turns to outright laughter.

All in all, a really good evening. It's in here for a reason.

One of the main differences between one era and another is the food. The mid-70s were a time when we had bathroom suites in various colours and called the green ones avocado, but didn't know what to do with the thing they were named after.

There. This whole chapter's been leading up to that. Tells you a lot.

*

The dessert was easier to eat.

Always amazes me how human beings arrived at certain foods. Raw wheat is no fun to chew, but someone decided if you ground it into a powder, then added hot water and maybe salt - and what's this disgusting thing called yeast? - you could end up with different kinds of bread.

You drink the milk of an animal because you're desperate, decide you want to keep doing that, then find some that's curdled but you're hungry so you have to consume it anyway and you think oh not that bad and you start making butter, then cheese, then leave the cheese till it goes mouldy and call it blue and eat it anyway.

Add cold butter to flour, which you wouldn't dream of eating on their own, mix in some sugar, and you eventually arrive at black forest gateau. How did anyone imagine that was going to happen?

If milk turns thick and looks yuk, fuck it we're hungry, call it cream. Mix it with raw egg yolks, which are disgusting to eat, add lemons, which are too sour to eat, whip it around for no reason you can think of, and you produce the latest miracle: lemon mousse, another exotic dish entering our lives in 1976. I haven't had one since I turned vegan twenty years after that, but it's still my all-time favourite dessert - and this was the best I ever had.

One of the college chefs was young and pretty. I found out it was her who made the mousse when I asked her to one of our gigs.