17. taking over the asylum

For most of his adult life, my dad worked in one of those big mental hospitals we used to have. Thirty-five years, then retirement at sixty.

He started as a ward orderly, a cleaner, brought over from Italy to do a job the english didn't fancy. It's what immigrants do.

He met my mum there, and she pushed him into studying for his nursing exams. Without her, he'd have been an orderly all his life. A small timid man, the youngest of thirteen in his family. Instead he became a charge nurse, on various wards. Power he wouldn't have had elsewhere (except over his own kids) - which he enjoyed a bit too much sometimes...

*

I inherited some of his reticence, but I never wanted to boss anyone about.

In my last year in advertising, our creative group was joined by two young guys from Lancashire. They had peroxide blond hair, years out of date in London. My art director, Bald Eagle, predictably called them Blondie and Sting.

Early on, they asked me to check a radio ad they'd written. Apart from one bit of grammar, I didn't suggest any changes. They were good.

Another time, they came into our office at lunchtime.

Cris, it is alright for us to go for us dinners now?

I told them. No need to ask permission to go to lunch. But if you do, the one person you don't ask is me. The only instruction I ever gave at work was instructing someone not to ask for instructions from me!

*

I presume the victorians built those mental hospitals. They built just about everything else. Museums, workhouses, public cemeteries, sewage systems. Putting some order into the empire.

And putting people away so others wouldn't see them. To this day, most people aren't comfortable with the sight of fellow human beings with visible brain damage. Better to stick them in an old victorian mansion in the woods, at the end of a mile-long drive.

These weren't psychiatric cases. They were born handicapped, some of them physically as well as mentally. Subnormal was the official term when I worked there. Before that, they'd been cretins, imbeciles, and moral defectives. People with Down's were mongols.

By the time I stopped, patients were called residents. Before long, these places closed down and their residents were in community care, which is how it should be, despite early scare stories in the right-wing press.

While they still existed, the big hospitals were worlds of their own. Part of mine too.

My dad's place, Borocourt, a few miles north of Reading, had its own gym, with a small swimming pool, football pitches and tennis courts, a occupational therapy unit, and a factory.

I always wondered about using mental patients to work in factories. They did the same work as millions of other people - we had a lot more manufacturing in those days - but I suspected they were paid a pittance like prisoners rather than getting the going rate.

Those big hospitals threw everyone together as a kind of job lot of the mentally handicapped. People with Down's or mild learning difficulties lived alongside people who couldn't talk and wore incontinence pads all their lives, or had violent mood swings. Community care came far too late for many of them.

The likes of Christine Badger, for example.

She was one of my dad's favourites. In later years, she sometimes stayed the night at our house, and he'd take her for lunch at Woolworth's, a common treat at the time. In return, she worshipped him. Followed him when he moved wards, cleaning and washing-up.

I imagine she was born around the time of the First World War. She was what they called backward, simple. But she looked after her ageing mum and had a good enough life. Then her mother died.

When they put Chrissie in a home, she didn't know what was happening to her. Distraught without her mum, she smashed some windows - and that was her for life. She lived out the rest of her days at Borocourt, which left her institutionalised like so many others. I think she was there for over forty years.

From the start of my life in England, she was part of it.

That's why I never flinched from people with visible handicaps. Some of my mates were genuinely scared, but I grew up around those people, from the age of three.

Both my parents had to work, and people couldn't afford childminders. So in the school holidays my dad took me to Borocourt a lot.

I liked it there. Tea and toast, which we didn't have at home much (italian household). Looseleaf tea through a strainer, milk and two sugars like everyone else in the country. The woods were huge, and I'd play in them for hours, happily on my own or with other kids who lived in the staff houses - and sometimes with patients themselves.

For many years, my dad worked in the adolescent unit, and I'd organise sprint races between those boys, some of them ten years older than me. Or we'd play pirates round the back, on the steps leading through a garden to the playing fields. Cricket on the lawn. I was an early sports therapist!

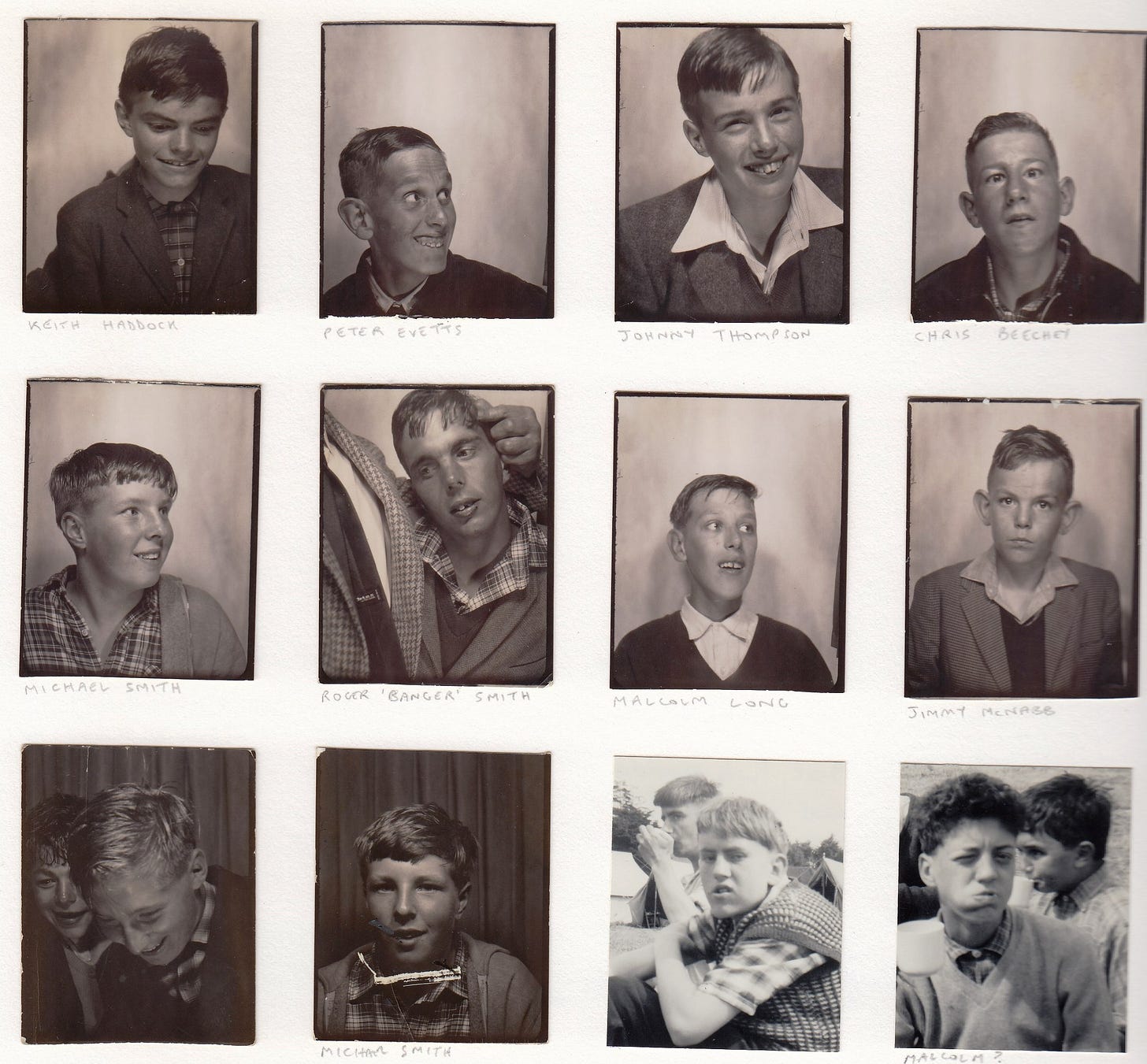

I remember most of them very well. Christopher Beechy had cross eyes and a speech issue but was brainier than he appeared. So was a tall kid called Malcolm, who had a stutter but could hold conversations with you. Another Malcolm - Malcolm Long - and Jimmy McNab and Keith Haddock, Michael Smith, Peter Evetts.

Brian Waite had a Berkshire accent, so when I was little I thought his name was Brown White. None of them needed medical attention very much. They would've thrived in community care.

Others weren't so lucky. Roger Smith couldn't stand up, so he'd sit on the floor waving his head from side to side. I was dead wary of him, because if you got too close and he was in a mood, he'd head-butt you. Banger Smith.

Johnny Thompson was toothy but good-looking, always happiest when twirling pieces of card on a string. And Emmerich Lehar was a beautiful lad but a sad case.

You'd be out on a walk through the grounds, patients and a couple of staff, and someone would say 'Where's Emmerich?', then you'd run to the long jump pit. Emmerich liked to eat sand!

That's not the sad bit. His dad was descended from Franz Lehar, the composer (The Merry Widow). He may have been Emmerich's grandad. The money passed down the family, and Emmerich's dad was seriously rich. So he could've afforded to keep Emmerich in Austria. Instead he dumped him across the Channel and got on with his other fifteen kids or whatever it was.

He visited Emmerich about once a year, around his birthday. Emmerich couldn't speak, but he recognised his dad every time, and he'd go into spasms and grunts - tragic to see, according to my dad. Especially one year, when he came home incandescent with rage.

Not only did Emmerich's father stay only a couple of hours, before the next long absence, he left Emmerich a pound. One fucking pound, from a man made of money. My dad had tears of fury in his eyes.

Emmerich Lehar was a harmless kid, Royston C Nutt less so. He didn't like men with long hair, and I once had to go to the doctor's after he sank his teeth into my upper arm. The soft bit underneath, hurt like fuck. I had to go to the doctor, who remembered it years later. Would you believe it, a mental patient called Roy Nutt.

My favourite, Barry Hirons, introduced me to the best rock band. There, back to music at last.

*

They got pocket money, those lads. They may even have had a wage, though I don't know if the factory had started up yet. But it wasn't enough for everything they wanted. So they found other ways to acquire it.

In Reading town centre, you could always recognise a group of Borocourt boys. They all wore long grey coats, with trousers that stopped short of their shoes. I recognised a group of them in a shop in Covent Garden, years after I'd moved to London.

Maybe there wasn't enough money to replace clothes they grew out of. But they made the long coats work for them.

They cut the bottoms out of the pockets, so everything slipped to the bottom of the coat. Amazing what you could fit into that space. They nicked sweets from the Woolworths pick 'n mix, batteries, playing cards, singles records. Especially the records. They cost several shillings each, so deep pockets came in useful.

I did it myself at secondary school. Unpicked the pockets in my anorak. I once had two James Bond paperbacks in there, plus packets of cards for revision. Got away with it so long I grew cocky. When a store detective nicked me, I got expelled and ended up in the shit boarding school. I don't regret shoplifting (there was never enough money at home), just wish I'd done a runner when I got caught and the headmaster hadn't been such a cunt.

Like me, the Borocourt posse got caught from time to time. But they were smart enough to know the police weren't going to be called for some stray mental patients. All that happened was slightly apologetic phone calls to my dad from Woolies or Heelas. In the end, he started searching them when they got back, confiscating any ill-gotten gains. But they were no fools. They simply hid their contraband in the woods, then went out to retrieve it when his back was turned.

Among their stashes: an item that changed my world view of music.

*

I'm ten years old when the damascus moment arrives.

Every ward had a record player. One of those with the speakers inside. A tinny sound with no bass to speak of, but it was all we knew. The one on my dad's ward was kept on top of a tall filing cabinet in the office, taken down for patients to listen to in the main room.

One day I'm in the office on my own when Barry Hirons and Chris Beechy come in, very keen to introduce me to something. Cristiano, listen to this.

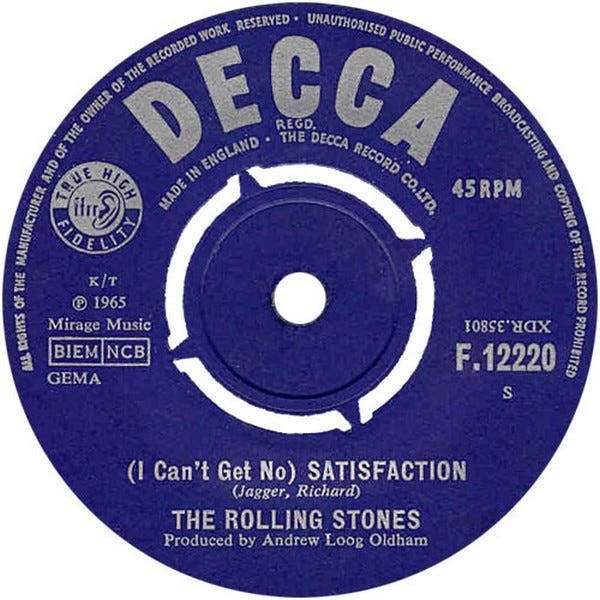

The lid of the record player had a number of 45s on it, and I'd heard them all. Leader of the Pack; Terry by Twinkle. But this was something else.

Barry got the record player down, put the disc on - and changed my life.

The opening riff came from a fuzz guitar. I didn't know that's what it was, but it sounded like nothing I'd heard till then, rough and dangerous.

Dur dur, dur dur-dur.

You're right: the opening to Satisfaction. I'd heard the Stones' Little Red Rooster at school the year before (I can still smell the dark pink soap sticking to the wash basins), but this was the first track of theirs that made me think there was something different out there. Before that, it was all Beatles.

I can't stand them now, but when I was seven a Beatles EP was the only record I owned. Twist and Shout rocked a bit (though it sounds like a rip-off of La Bamba), but the other three songs must be McCartney because they're all treacle. Do you want to know a secret, There's a Place, A Taste of Honey. Harmonies and all that bollocks.

I got it as a birthday present, along with a Beatles wig, which was made of hard plastic and hurt your head, sitting there like a lump of toffee.

In 2002, I went from London to Orkney to see a rare bird. The guy who drove us all the way there and back was Colin Wills, a journalist who'd just retired. He was about twelve years older than me, so when the Beatles became famous he was nineteen or thereabouts, and I was interested in his view of them.

When they first appeared, what did you think?

He dismissed them in two words. Boy band.

You can't put it better than that. Their easy-listening love songs. Then they vanished into the studio via their own arses. A boys' band. I liked them when I was seven.

For me, Satisfaction swept the pop groups aside. I discovered the Beatles at primary school, the Rolling Stones in a mental institution. Says it all.

Over the years, I've thought of the Borocourt Boys quite a lot. The Barry Hirons who died in his early thirties in 1978: hope with all my heart he wasn't my man and they all had good lives after they left.

*

The reason for mentioning that hospital at all, let alone at such length? It was the venue for an important event.

I found myself there in early December. Maybe I was starting the latest stint as an orderly during the christmas break.

The social secretary wasn't much older than me. A big friendly guy with a full beard, Matthew somebody. Soft-spoken, bit of a hippie, used to go to Glastonbury.

Before 1976, my main memory of him was a night I spent on his floor.

*

In 1962 we moved house. They pulled the old one down after we left, the whole terrace. Outside toilets and no bathrooms.

We crossed the river to Caversham, a part of Reading that's geographically in Oxfordshire. The street through the centre has shops on both sides. On one, there's a smart old library. Behind that, parallel with the main drag, lies a short street called Rectory Road. I think that's where the doctors' surgery was, when I was bitten by Roy Nutt.

But Rectory Road was more important for other things. I remember it very warmly. One of the houses is where I started meeting women.

Nurses from Borocourt lived there. Two of them told me I was good-looking, which I hadn't heard before. It's where I slept with a girl for the first time.

I was eighteen when I went to my first party there, and Georgina Rokvic announced that the handsome wops had arrived (I was with a guy called Romeo). She was half-italian herself, half yugoslav, a few years older, bit of the Gina Lollobrigida about her. I dated her several times, but she was saving herself. Years later, she told me it hadn't been worth it. Wish she'd let me do the disappointing!

She was one of the Borocourt nurses, though she didn't live at Rectory Road. Maggie Guppy did, the first girl I spent a night with. Again, a couple of years older than me.

She worked at the mental hospital too. Her brother Ben was a charge nurse on one of the wards. There was a particularly steamy new year's eve party up the hill in Emmer Green, in the White Horse, which was right across the road from the Black Horse. Ben Guppy was the tallest person I'd ever seen. At the end of the party, he took it upon himself to french-kiss everyone in the room. You don't forget being snogged by a bearded six-foot-seven Sugar Plum Fairy in a tutu. A great night. I didn't know Maggie for long, but we had a soft spot for each other. Ben was a class act too.

After another of those pub parties, I came back to Rectory Road again, and it was packed with people crashing out. I ended up on a floor with the girl I was seeing, next to big Matthew's bed. I sincerely hope he fell asleep immediately, because we didn't. I remember praying he wouldn't hear her undoing my belt buckle. We were full-on, ending with a climax we tried to keep quiet. Matthew didn't make a sound, so here's hoping.

*

When I bumped into him at Borocourt in late '76, the chance encounter bore unexpected fruit.

I knew he sometimes put on parties for the patients, in the ballroom at the main house. So I thought I might as well ask...

Don't suppose you want a rock band?

Not sure we can afford one.

Don't worry about that, I said.

*

Thursday 16 December 1976. The day of the Borocourt concert started at 88 Banbury Road.

Two cars for the short trip through Oxfordshire. Four of us in Patrick's, most of the gear in Harry's. He drove a blue Renault 4, a right little narnian wardrobe, amazing how much you could get inside it once the seats were down. But this time he attached a small open-top trailer on the back, to carry the speakers.

He had a passenger in his front seat. He'd come back from France with this car - and a girlfriend. Suddenly there was a blonde amongst us.

I couldn't remember seeing Harry with any girls in the first year, but this one was a benefit of his time abroad. She was called Odile, and her appearance allowed Bernie to maintain his theory that french women were 'all nose and knockers'.

Like Bardot, you mean? Leave it out.

She's got 'em too.

Don't know what mademoiselle thought of travelling to watch a very average band play in a mental home (I didn't talk to her much, even though I was studying her language at college: my spoken french led to remedial lessons) but the evening went well enough. We knew more songs by now, and my voice slipped through unnoticed again.

*

It's only just struck me, writing this decades later, that I was about to perform on the same stage as my dad.

I said he was a good singer in his youth. His voice hung in there over the years, and I watched him at two christmas shows in the hospital ballroom.

I was a kid and they were fun, like old music halls events, a lot of laughs - though the place went into a reverent hush when my dad sang. Ave Maria (which we got someone to sing at his funeral), Panis Angelicus, and something about a donkey carrying the Virgin Mary. Standing up there in his suit and sounding good.

Proof that talents aren't always handed down.

When I phoned him one day, I remembered something in passing. Oh, by the way, I'm in a band.

Now, band to him meant big band, so I had to explain it was one of those new-fangled electric groups. Guitars, you know.

He was genuinely nonplussed. Imagine a strong italian accent:

But you don't play instrument.

I know, I said. I'm the singer.

You know that silence? When someone's laughing so much they don't make a sound?

Alright alright, it's not that funny.

Oh it is, he said. It is!

I don't know if he was at work the day the Milkins played Borocourt. He certainly didn't come and see me tread the same boards!

*

It was never going to be a Difficult Second Gig.

Let's face it, kids with learning difficulties won't be your harshest critics. They're just happy to hear loud live music, a real novelty for them, and to dance a bit.

Before Jailhouse Rock, I called out 'Who likes Elvis?' and got a chorus of approval. When I told them our encore had a naughty word in it, they cheered.

No photos this time (story of our lives in our twenties), so there's not much to trigger my memories (no idea what we were wearing, for example) - even though I looked at my surroundings a bit more.

One of the photos from the opening gig shows me staring down into the microphone while I sing. That was a habit I picked up in rehearsals. Don't know why. Because I didn't want to see lookers-on who thought I was crap? I honestly didn't care about that. But I kept having to remind myself to lift my head and look at the audience, and I did it that night at Borocourt.

I remember a teenage Down's girl dancing on a table close to the stage, stamping one foot then twirling her whole body round it, like a spinning top, a marvellous little mover. Wonder how her life turned out. She shouldn't have been in a place like that.

The set was the same as our first gig, plus another Chuck Berry and three more Stones songs, including Midnight Rambler, which had nearly ended my singing career before it began but padded out a gig for an undemanding audience.

We started the whole thing with an instrumental.

Not a bad idea, you might say, with a singer like ours. But it was probably to ease the Borocourt kids into it, to get them used to how loud a live rock band can actually be.

The track came out of musicians mucking about in rehearsals. A nonsense song with words we really didn't want to repeat.

Moses supposes

His toeses are roses

But Moses supposes

Erroneously

No idea who wrote it or why, and I'm not about to look it up. The tune shuffles along, Bill using brushes and tisking the high hat. Because we left the words out, we called it Without Moses.

What was I doing while the musicians were playing this thing? Maybe shaking maracas nobody could hear. After that, we led the kids in gently with Not Fade Away.

Our encore was the last track on Goats Head Soup, puerile and lazy but a rocker, and we knew today's audience would enjoy the rude word.

It's called Star Star because they weren't allowed to have Starfucker on the album cover. Naturally the BBC banned it.

It's about a groupie, of course, with a reference to givin' head to Steve McQueen and immortal lines like

Your tricks with fruit

are kinda cute

I bet you keep your pussy clean

God dear. These were fully grown men, in their thirties. They'd just had the best four-album streak in rock history. And they write stuff like that. A chorus with the word starfucker over and over. The novelty eventually wore off and we dropped it from the set.

But it was exactly the right thing to end the Borocourt gig. The kids had a good time, so Matthew was very pleased. So much so that he suggested we could play there again, for the staff this time.

Woo. I could never have imagined that in a million years.

As a teenager, I'd looked in on one of the big staff parties in this ballroom. A disco, proper rock band, and a lot of nurses. I was too young to go out with any of them, and I certainly never imagined I'd be in one of the bands that played there.

Now Matthew's really saying we could? For the nurses as well as patients?

Definitely.

*

A couple of us spent the night at my dad's house in Reading, which opened Bill's eyes to how the other half lived.

Bill Drysdale came from Harpenden, in Hertfordshire, among other families with money. He was mates with Eric Morecambe's son.

My dad's place, where I grew up from the age of seven, was a semi-detached with four bedrooms, so a sizeable property. But he'd let it run down. Living with just my brother full-time, he didn't feel the need to decorate. Not just upstairs but the front room too. The wallpaper next to the door used to have a dark line, where the dog rubbed the wall on her way in, like Phil Squod's mark in Dickens. When that strip of wallpaper began to curl up at the bottom with age, my dad let it. In the end, you could cradle a baby in it. He replaced it eventually - but when he retired, there was bare plaster on a wall in the kitchen. He cared more about his garden. When we were kids, there was only a small area to play in. The rest was his fruit and veg.

The two bedrooms on the top floor, the converted attics, used to have my sister in one and me and my brother in the other. When she got married, we got a room each, me in the one we'd shared. Can't remember if Bill Drysdale slept on a mattress or the single bed, but he must've raised an eyebrow at the state of the house and all the junk my dad kept. He never threw anything away. When he died, I found all my school reports, several odd shoes, and a bag full of broken zips! Don't ask.

Next to my bed in '76, there was a crude bedside cabinet, a horrible piece of unpainted wood. On the side, facing you as you came in, I'd scribbled '...and cracked like a curate's egg'. We know what a curate's egg means, but why I wrote it on there, given that no-one would ever see it...I think it had something to do with the bad novel I tried writing.

We had a drink before bedtime, and Bill surprised me. When we'd first started rehearsing, he said, he worried it wasn't going to be good enough. Not just my singing, the whole thing.

Don't blame you -

But now, he said, he was proud of it.

Woh.

I never expected that. Proud. After just a couple of gigs. Hearing it gave me a sense of, well, pride. I'd already achieved something.

Wonder what Bill would think if we ever played for a more discerning clientele. But I had the feeling none of us would be fazed by that. We just wanted to keep getting up on stage.

*

Naturally we didn't charge the hospital for our services. But Matthew kindly gave us a fiver, though I tried to refuse it. A whole pound each, which went towards the petrol.

Never thought we'd turn pro so soon!