57. writer's reign

Music was never my rock 'n roll.

I’m a bad singer but a good writer. When I can be arsed.

I've had things published. This chapter's about that. Because it's something I did well at times, I'll probably sound like I'm blowing my own trumpet (musical reference; told you I was in a band). But, as always, you can jump to the next one. There's a really crap singer in that.

*

I didn't start writing fiction properly till I left college.

I'd been good at essays at primary school and just beyond. We were encouraged to tell short stories, and mine went down well with teachers. I remember the old nun who taught us in our final year telling the class that one of my efforts was a cut above because it started with 'Having' or some such, a kind of participle. I still don't know my grammatical terms, but apparently this was unusual for someone my age.

In the first couple of years at grammar school, we were still given fiction to write One of my teachers said he enjoyed my stuff because it always had food in it! I may have got that from CS Lewis and James Bond. I'm told my essays in detention were good too!

After that, though, it stopped. From the age of thirteen or so, no more stories. Just factual essays, in english as well as subjects that don't require fiction.

In my first year at Oxford, I began a novel. No idea what it was going to be about, no plan except to set it in the countryside. I remember sitting at the small desk under the window in my room across the road from college.

But I didn't get further than a few lines. A row of poplar trees formed 'a resigned rank of windbreakers'. Then college life and laziness intervened.

Apart from that, a few duff poems to go along with Rick Bowden's - otherwise not a word.

It took a girl to change all that.

*

Soon as I moved to London in 1977, I earned proper money at the ad agency, though not enough to buy my first flat till four years later (other guys I worked with, they had rich dads), and even then only because I topped things up with my first attempt at fiction.

The blonde I started seeing when I came to town, we were together for a couple of years. She was happy working as a secretary for the Racehorse Owners Association, but she dreamed of owning one herself some day, and had the name of her horse ready: a little colt to be called The Hustler. One of her birthday presents from me was a history of the Derby. It was a romantic evening, honest.

But early on I saw something she'd drawn, and it was her talent that got me writing properly at last.

In my early teens, I'd started a story about a badger. I called him Meles, from the latin name (I tried to be a bit more original after that), and read the first few paras to my brother. But I had no plot in mind and wasn't really interested, so I left it at that.

It wasn't till 1978 and the Blonde's sketchbook that I thought I really should get the writing act together. Listen, I said, I've got a couple of animal stories in mind. Why don't I write some and you do some drawings for each one? Then we'll try and sell them.

As well as the mansion in Haywards Heath, her dad owned a holiday cottage in Criccieth, north Wales. She drove us all the way there, and we used it as a base for touring the area. Portmeirion, Llanfair PG, Lloyd George's birthplace, and various castles: Harlech, Caernarvon, where we did our thing, and the ruins at Criccieth itself. The weather was damp and grey most of the time, so we spent plenty of time at the cottage, her sketching indoors, me apparently wasting time outside.

From the room where she was drawing, she could see me in the small garden, playing pitch and putt with a golf ball I'd found. It may have looked like I was idling while she worked hard, but she knew I was using the time to think of plots for various animal stories. Dialogue too, which involved talking out loud in voices an adder and dormouse might have. She was indoors, so she didn't hear me do that, but she would've enjoyed listening to it. Laughter was her default activity. Apart from the bad migraine she had one night, a warm and productive week.

Her sketching technique was something I never saw before or since, very effective but incredibly labour intensive.

When she drew, say, a clearing in a forest, she wouldn't do a pencil wash, something impressionistic which would've been perfectly acceptable. Instead she smudged the whole thing with a rubber - after drawing every single blade of grass!

She was good at animals too. The grey squirrel and hedgehog in the opening story, with a pair of vicious badgers (which is how they are with hedgehogs; forget Meles or Wind in the Willows) - and an owl with burning eyes in the second one. When we broke up, I offered to buy all four drawings, but my offer was derisory, so all I've got is photocopies. Mistake on my part.

A few years later, in the early Eighties, another girlfriend also painted that owl, as a surprise birthday present. A masterful close-up in oils, all the plumage details, with its wings spread and face right in yours, still coming for me in my living room.

I do own an original by the Blonde too.

In the summer after I left college, I bought the Reader's Digest Book of British BIrds. I didn't start birding seriously for more than ten years, but I'd always been into wildlife (an A for nature study at primary school), and I liked the colour plates in this thing. A hefty tome, heavy enough to kill a cat.

One of the illustrations features a great tit, a common enough species but one I hadn't identified at the time. The Blonde produced a pencil drawing of this. No colours but a perfect repro (feather by feather, of course). On the back, she wrote 'This bird is a GREAT TIT - unlike the bird who loves you'. OK, obvious jokes, but I loved her back for it. It looks great in an antique wooden frame in my study.

By 1979, I'd written thirteen stories in all. Whenever I finished one, I read it to Robin, who was also my sounding board for the novel that followed. Reading aloud clears away the bullshit. You get embarrassed using 'literary' language in front of someone. So it was a useful thing to do. The Blonde liked the tales too. Now to see if an agent did.

Robin was useful in more ways than one. His godfather was Jimmy Fraser, who founded Fraser & Dunlop, one of the biggest theatrical and literary agencies in London. Robin's dad was one of his clients, as an actor and writer.

Look up Jimmy Fraser and you won't find a trace, which I've never understood, because he was a major figure in that sphere.

Jimmy was a sixtysomething gay scot who could be camp when he wanted. And a tough-guy agent. He had to fire one of his clients one day.

He was late for dinner at Robin's parents' flat because he had to sort it out. The guy's been telling him he isn't getting any work because his agent's homosexual!

I can picture Jimmy giving him a long look, then replying in that light scottish voice, like a soft-spoken snake. He repeated his response in front of us: Darling...the reason you don't work is not because your agent is homo-seksual...but because you've got no fucking talent!

Jimmy Fraser was always entertaining but no lightweight. So when Robin gave him my manuscript, I thought it might hstand a chance.

I wrote each story with a black felt-tip on the lined yellow pads we had at the advertising agency. Then typed them on the Adler in my office. I'm bashing one out when my boss comes in. Uh-oh, caught doing extracurricular naughties when I should be thinking of commercials.

He glanced at the paper in the typewriter, then turned the knob to bring it up. Now I'm going to get the sack.

Freddi, that's the best thing you do. He didn't suggest I give up the day job, but that's what I did a few years later.

The Adler was a metal monster, heavy enough to do arm curls with. The keys were so leaden I used only the middle finger on my right hand, supported by the thumb. I typed a book of short stories, then a novel, with one finger! The mighty machine rests in the garage now, a monument to a triumphant age.

typewriter ribbon. Hit the blue and you type in blue or black. The whole thing weighs 18 kilos.

When all the stories were ready, I spent a week at my dad's house in Reading typing them up properly. While I was there, I had an idea for an extra one, about a cuckoo, which was the last thing I wanted (the actual writing has always been a bane). But I wrote it in two days, then put them all in a black binder that didn't need clips, you just pulled it back then let it close over the edges of the sheets of paper. Each story was separated by a sheet of yellow paper. The binder has a surface like an old leather-bound book. The original typed pages are still in it, still a prized possession.

Back in London, I sneaked into the photocopying room at the agency. The same boss once told me to stop creeping around like a criminal. If you go home early, use the front exit not the back stairs. But I needed those back stairs when I filched an entire filing cabinet as I left the company! And I photocopied several copies of that book.

Now sit back and wait for Jimmy Fraser to call. Took him six months!

Nowadays that wouldn't happen. There seem to be millions of agents out there, you can contact them quickly, and if they like your work they'll show it to publishers just as fast. Things moved at a different pace in the days before emails - and anyway Jimmy generally handled actors, not writers.

But six months, for fucksake. I told Robin it was time we tried to sell the book ourselves, send it to publishers. Hang in there a bit longer, he goes. Jimmy knows what he's doing.

Sure enough. The stories were set in a british forest, but Jimmy thought it might appeal more to americans.

He knew an agent called Gloria, whose surname was spelt Safier but pronounced Sapphire. Imagine that: Gloria Sapphire, like a Hollywood star of the Thirties. One day I'm at work when I get a call from New York. Not from her but another woman, an editor. She tells me she works for Knopf. You know about us, of course.

Er, not exactly. I'd heard of only a couple of publishing companies, and none outside Britain. I just didn't know that world at all. She was genuinely taken aback. We're the biggest in the world!

Oh. Well, that's good.

When I put the phone down, I turned to my art director. I'm going to be an author, I said.

Knopf paid me an advance of five thousand dollars. Not bad for those days, and anyway fuck did I care. Rubbish college poems aside, my first attempt at fiction was going to come out in print. They could've offered me zero and I'd have bitten their hands off.

I used some of the proceeds to take Jimmy and Robin to lunch. A couple of hours basking in my success.

I believed in the product, Jimmy says. Just when you were thinking let's take it away from the old bastard and do it ourselves...

Me: Perish the thought, James.

Robin, grinning like a fool: Yes! Yes, that's exactly what he said.

Oh, thanks, pal. With friends like these...

Jimmy Fraser really was formidable. When I ordered a half-bottle of champagne, he actually pouted.

Half a bottle, he says archly....

Well it was quite a posh place, and I wasn't used to paying a bill that size. At the agency, lunches were on expenses. But of course I should've had a better sense of occasion. Made sure I took a full-sized bottle when he invited me and Robin to his flat one night.

Have to say Jimmy Fraser didn't like spending money either. He was almost the cliché of a tight-fisted scot. When he bought Robin an expensive pen, Robin nearly fainted. Jimmy did leave him enough in his will to pay off a mortgage in Australia - but he enjoyed saving on the little things. One day he comes into Robin's parents' flat brandishing something.

Look at this, fellas. He'd just turned 65.

What's that, Jimmy?

Bus pass. Isn't in wonderful?

Jim, I said. You can afford a fleet of buses.

I know, he goes. But I love getting on and waving it at the conductor. You cannae touch me!

In those days, a bus pass was just that: you couldn't use it on the tube. But Jimmy didn't mind taking longer to get around London if it saved a few quid.

He even served stale crisps at his party!

Robin was invited as Jimmy's godson. I was asked along to meet Gloria Safier. She turned out to be a classic tough old american broad, just what you wanted in an agent. And she had someone in tow.

When she arrived in London, she brought me a copy of a novel by one of her authors, published the same year. It was a thriller, and I don't do thrillers. But I read it because she asked me to, and it was so good I finished it in two nights. The attention to minute details: I knew I'd never want to write like that, but it was masterful and I told her so.

The novel was called Red Dragon. Written by Thomas Harris, who went on to Silence of the Lambs. It was him at Jimmy's party with Gloria. Beard and glasses.

I was about to tell him his book was really good when he said mine was! Great piece of work, Cris. I was so surprised I could barely get out a 'Yours too' before the pair of them left. Maybe he was just being polite, but I don't care!

Both our books went on to be published in paperback over here, by the same company, Corgi, though of course they paid him a massive advance which they knew the book would never earn. Authors that big are loss leaders. Publishers want their names on their letterheads.

In a coincidence you couldn't script, my editor at Corgi had been to my horrible boarding school.

I saw Gloria again before she went back to New York. She was the only woman at Jimmy's party. Some familiar actors, presumably Jimmy's clients, like Victor Spinetti, who came from italian stock.

After a while, I had a look round the room and something dawned on me. Rob, I think we're the cabaret here...

We were the only ones under a certain age and maybe the only heteroes. We got some admiring looks and entertaining chats and it was a good evening.

*

They never used any of the Blonde's drawings.

The book came out after we split up, and I took her to lunch to give her a copy. Hm, she said, these illustrations look a bit like mine...

They did, too. And I felt bad about that. But it really was just a coincidence. The publishers already had someone well-known in mind. A shame, because hers were much better.

I tried once more, when it was published over here. Again they used a different illustrator, again they got it wrong. I'd have loved to see her name on the inside cover.

Hope she carried on with her drawing, because the craftsmanship was a thing to behold. Every blade of grass!

Last time I looked, she'd been married to a clergyman for over 35 years. I guarantee her husband's had a great life in this world.

*

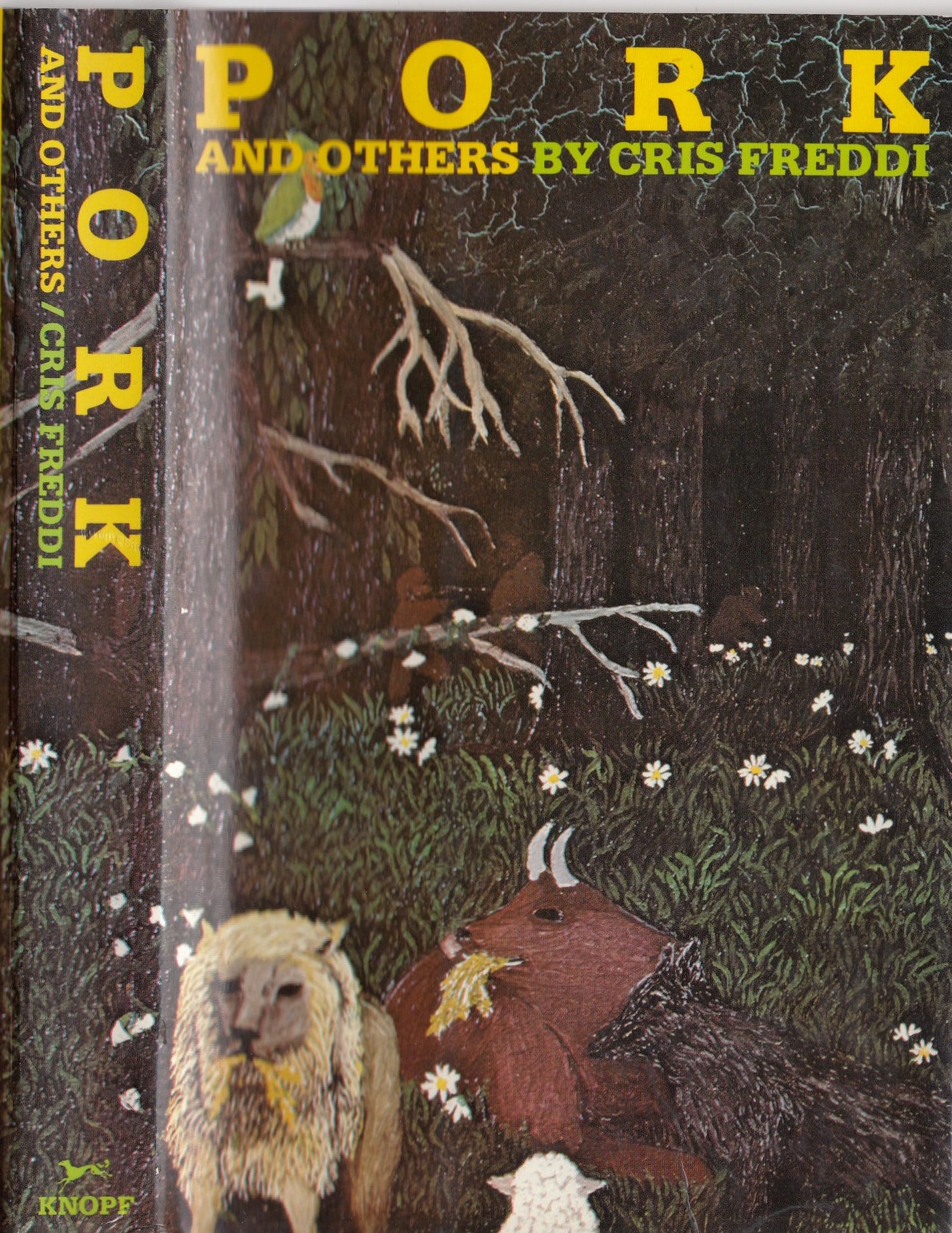

At least Knopf got the front cover right.

A detail from a picture painted in primitive style, with animals in the foreground and shadowy hunters disappearing into a dark forest behind. I thought it had been painted especially for the book, so I asked if I could buy the original. You can try, they said - but it's in the Metropolitan Museum of Art!

I'd never heard of Horace Pippin. I didn't even know he was black until 2018, when my son's class had a lesson on him in primary school. That ended before I knew about it, otherwise I'd have offered to show them a copy of the book, which would've embarrassed the hell out of my kid. One of the perks of being a dad.

*

I called the collection of short stories Pork.

No more original than Meles. Pork's the name of the main character in the first story, and I took his name from what he is: a hedge hog. Dear critics, I was only 23.

At least the name worked well as the title of a book. Short and punchy and intriguing. But the editor wanted to make it clear this was a book of stories, not just one. So she insisted on adding 'and others'.

Now, that works on the cover, where Pork's in bigger type. But reviews referred to it as Pork and others, which doesn't have anything like the same impact.

It was like that in advertising sometimes. You'd write a script approved by the client, and some executive would fuck up the ending by making it more of a 'solution' and less funny. Our agency was known for that.

Pork and others is too literal, even a bit corporate. With that and the ads, I should've insisted. I didn't make that mistake with subsequent books.

*

Pork, and the others, came out in four editions, two each in hardback and paperback, in the USA then over here. Four different publishers paid me an advance for each of the four, though I didn't earn any more after that. Sales were never quite good enough.

A pity for the publishing companies, and I wished it had done better for them. But there's a long history of paying authors more than they earn - a lot more than me - and I have to say, purely from my point of view, the whole arrangement was fine.

All I ever really wanted was a copy on my bookshelf.

Hardback, with a dust cover, with an illustration in it, though paperback was fine too. I've had a few of each. From proper publishing companies, not self-published (it used to be called vanity publishing) or an ebook. Something I could look at and say 'I did that'. I never do look at them up there, but I can if I want.

When Pork was with an agent, I daydreamed of seeing it, several copies in a stack, in the window of John Menzies in Oxford. And miracle of miracles: it happened. But I wasn't there to see it! Someone told me.

I wanted to be paid for a book. An advance, however small (and I've had small as well as big).

And a good review or two wouldn't go amiss. A number of well-known american writers gave Pork write-ups that made me blush: Alice Adams, Scott Spencer, Richard Wilbur, Anne Rice of the vampire novels. And some major american papers were fulsome too: the Village Voice, Washington Post, Los Angeles Herald, Boston Globe. The book spawned comparisons with Kipling, Golding, and the dreaded Tolkien, 'with a dash of Darwin'.

After dozens of reviews ranging from very good to very very, I asked my editor if she was hiding the bad ones! There was only ever one - and I remember every word:

'Garrulous people-as-animals stories, bobbing along in the wake of Watership Down, where they deserve to sink'.

'I think they really mean it!', she said.

I tried framing it, but the print was too small!

*

Naturally you can't wait to hold your first copy of your first book.

I was living in Highbury at the time, and when a note came through the door saying a parcel had been taken back to the depot, I hurried over. Bit of a walk, too. When I got there, the parcel wasn't thick enough for a book. Les Milkins had arrived.

We didn't really have a band logo, but we stuck L plates on a couple of our speakers. This was a spanish one - green, with a white L - sent by Harry, who was working in Madrid. I admit to being a it disappointed it wasn't the book, but a nice thought of his. I kept that L plate for a number of years before it got lost in a move.

The novel turned up soon enough, and I remember a celebration dinner with my girlfriend and some good shrimps.The cover and spine of the book, in a dark green metal frame, has pride of place in my study.

*

When I used to read fiction, books were sometimes dedicated to someone. You'd see their names on a page of their own, before the first chapter. I liked that. When mine came out, there was only one person I wanted to dedicate it to.

I couldn't come right out and write 'To me'! Instead the name Les Milkins appeared on both my first two books. Because who do writers write for? It's always themselves.

I didn't dedicate the third one to anybody. By then, Les Milkins sounded a bit embarrassing, too much undergraduate humour.

But I still brought back the name. As part of the publicity for the novel, I wrote some blurb. Said I was born in Reading and went to school there (didn't mention the boarding stalag; I wasn't having that dump claiming any credit).

Then I added Oxford, 'where he was lead singer in the Les Milkins Band', making it sound like my main achievement there. Well, you know...

*

I had two best men at my wedding. In his speech, Robin referenced Pork but pretended he hadn't read it because he was jewish on his mother's side! Groan, but it got a laugh.

Many years after it was published, I got a call from someone who'd worked at the same advertising agency, another copywriter. He'd made his money writing other things, and now wanted to pursue a pet project, turning books he'd liked into ebooks. One of those was Pork. It didn't sell very well, but nice to be remembered after all that time.

*

Pork was my first album.

A collection of songs I sang in tune.

All because my heart was in it. I liked the forest I was coming up with.

I started the whole thing with a very short introductory paragraph. 'Somewhere in the damp deciduous north there was a forest like any other'.

For various reasons, all three words matter here. Damp, deciduous, and north. Especially deciduous.

I enjoyed visualising the landscape, especially the woods. Almost felt I was in there. The works of fiction after that were work, so I didn't put as much into them, though the last one's alright.

*

So my first attempt at fiction got published. I started it when I was 23. But if I'm tempted to get big-headed, I remember my son.

He wrote a poem for a competition at school. When it won, it was shown in the entrance halls of tube stations in London. He was seven years old.

*

After those short stories, what next?

I would've been happy starting a volume two. I even envisaged volumes beyond that, a Comedy of Animals to go with Dante's Divine Comedy and Balzac's Comédie humaine. I know, but I stayed young for a long time.

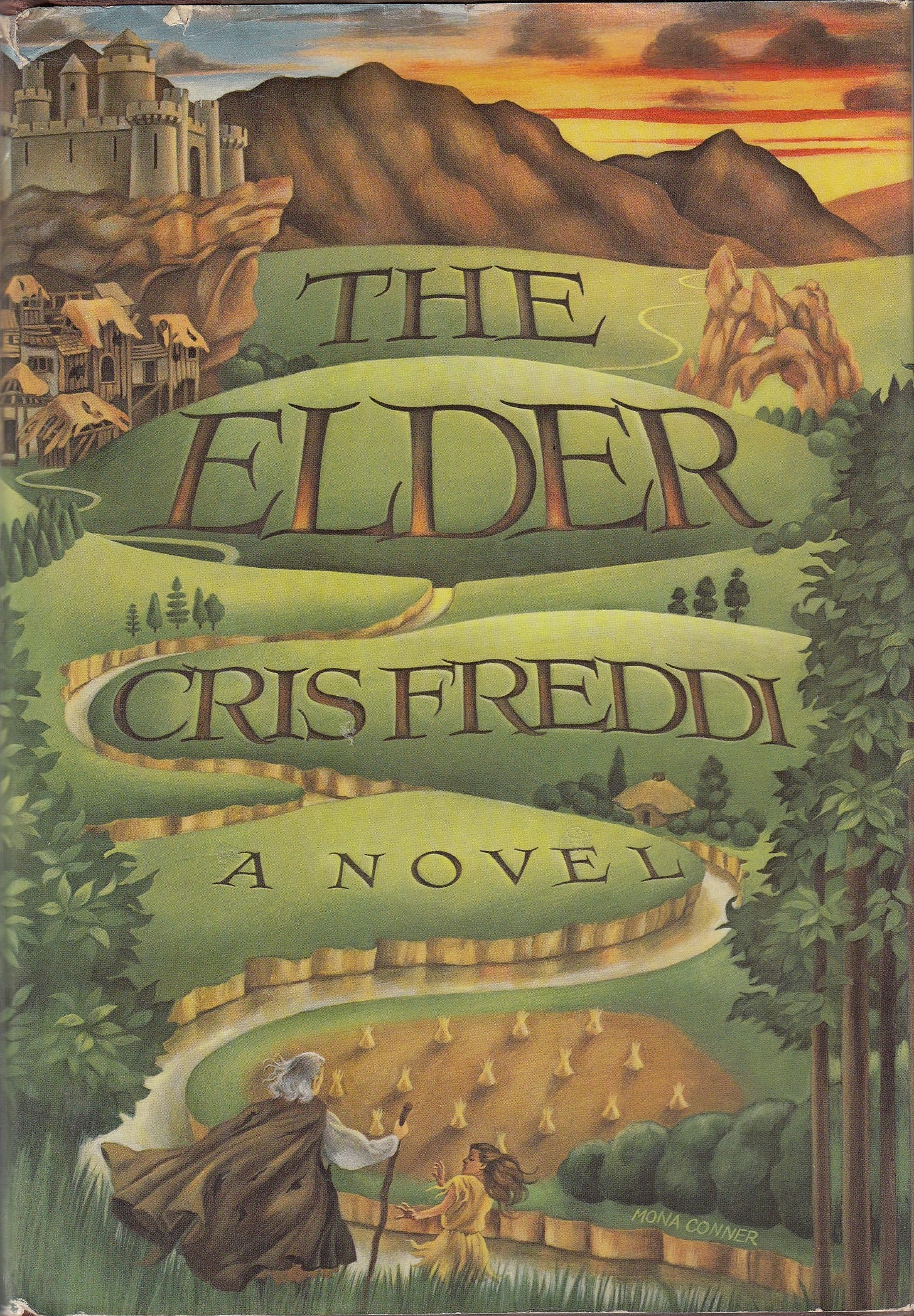

No no, said my editor in New York. It has to be a novel. So I had a go. But because I had to think about what to write, it turned into a difficult second album, though the initial idea was interesting.

I'm watching football on TV. Not an actual match but the fag end of an interview with the chairman of the FA.

Harold Thompson was a chemistry teacher at Oxford University during my time there. Before that, he taught Margaret Thatcher, so you had to hate him by association. But he was vile in his own right.

At the FA, he was an amateur lording it over a professional sport. By all accounts (I knew someone who worked there) he was a megalomaniac who treated staff like underlings. When Alf Ramsey was sacked as England manager, it wasn't before time, but Thompson handled it with no sensitivity at all. And of course he stopped Brian Clough from replacing Sir Alf: Clough would've taken over Thompson's fiefdom. An autocratic old cunt, a blight on the game.

Old being the operative word. When I saw him on TV that time, he was in his seventies, and I remember thinking how can someone that age be running an activity played by the young?

That sparked something. What if you could advance in life only by getting older? Geriatrics with dementia holding positions of power over the talented young. A valley where the chief was always its oldest resident, its Elder. So I wrote a novel with that name, and the american publishers published it. You've created a kind of Middle Earth, Cris. Eek, I hope not. I was a CS Lewis fan, not the other one, who didn't use one word when twenty would do.

Whatever I'd created, the first novel wasn't a success.

Pork hadn't sold in great numbers, but it launched that stream of glowing reviews. Publishers Weekly even called me 'an author to watch'. Yeh well.

The Elder got hardly any reviews, and no good ones. Can't say I was surprised. I'd handicapped myself from the start by making the only female character a mute! Don't wonder about the psychology: it was just a phrase that came into my head and I ran with it. Of course, it did the book no favours. Someone who's always written a lot of dialogue gave his protagonist, her boyfriend, no-one to talk to.

The premise wasn't bad. In a world run by the old, a pack of young guerrillas rise up in violent revolution. But it was a grim read, with zero warmth or compassion (shoulda let that woman speak). The book's there on my shelf, but when I framed the covers of things I've written, The Elder wasn't one of them. I'd write it very differently today. Might make a good film...

*

After the first novel, I didn't have a second one published for twenty years.

Before The Elder was even out, I came up with what I thought was a tremendous idea, but again I wrote it badly, and this time Knopf turned it down. Many years later, I tried again, with a different agent and a much better storyline and feel - but again no go. I still think it's a huge idea, but I'm in a minority of one, so it's probably crap.

After the first draft of that novel, nothing came to mind. For years. On end. No plotlines at all, not a single character. But that was fair enough:

I've always hated writing fiction.

By the time I had a second novel published, I hadn't read any in 20 years. Now make that 40 and counting.

If there's a way of saying that without sounding a smug git, I'd like to know it. But what can you do. It's a statement of fact.

Back in 1989, when I wasn't out birding I wasn't doing much at all. Wish I could say I stayed in to do some writing, but the truth is I hardly ever thought of it at the time. And I can't even claim writer's block. I didn't even try to write. Any ideas for fiction were crap, mainly because I simply couldn't be arsed to sit down and think them through.

Story of my life. Chronic laziness. Any subjects I found easy at school, I did well at. Anything harder and I didn't try (class sizes didn't help, and you were left to sink or swim). That approach can get you to university, but it struggles at making money. I got by with minimum effort in advertising - but, after the short stories at the start, fiction's always been a chore.

I can put one word after another (you've noticed), but the surprise isn't that I've had so little published, it's having anything in print at all. Too much like hard work. Sounds like I'm flippant about it, but it's been a lifelong issue.

*

What got me a second novel, a third book of fiction, was the telly again.

Sometime in the 1990s, I'm watching a news item on TV. It featured someone called Colin Watson, and what he said changed my life, though he didn't mean to.

In the Seventies, if I watched the six o'clock news at all, I'd sometimes linger for Nationwide, the magazine programme immediately afterwards. That's where I discovered the Portsmouth Sinfonia, which gave me the idea for a rock band. Many years later, again I got an idea from one of the very few times I watched the news.

Colin Watson was a well-known egg collector, an egg thief. By the time they confiscated his stash, it had reached two thousand wild birds' eggs. When I saw him on TV, he'd just been caught again. Fuck knows how much he paid in fines over the years, but that didn't deter him.

I remember him as tall, with pale curly hair, maybe a perm. Northern accent as he stands in front of the camera and tells us the authorities should let him keep his collection, then he wouldn't have to put another one together! Like a burglar saying if they let me hang on to these tellies, I wouldn't need to nick any more.

My first reaction: what a dim tosser. My second: they should jail these fuckers, which started happening in later years. But the actual words in my head were 'Mate, you want shooting.'

Now there's a thought...

Within a week, I'd written the opening chapter of a birding thriller. It involved an egg collector climbing a tree - and a narrator setting out to kill him.

It worked so well I hardly changed a word over the years - while the rest of the novel went through various convulsions. An agent liked that opening chapter, but I hadn't written any more than that. I just hadn't thought how the story might go from there.

Now, buoyed by an agent's encouragement, I wrote too much too quickly, with an ending as good as the opening but pork pie filling in between. The result was a predictable disaster. It still had enough about it to get me a chat with a publisher, Penguin no less, but it was a mess and I couldn't put it right. The same agent got me a World Cup book, and I forgot about birding thrillers with egg collectors in them.

But that first chapter nagged away in the back of my mind. There's a good idea there somewhere - you just fucked it up. Drag yourself back to the coalface.

Long story short, I rewrote it completely and three different agents wanted to handle it. That led to three different publishers wanting to buy it, and it made me some serious money at last. Just half the advance was more than I'd ever earned in a year.

I was at Mad Mart's flat in Italy when my agent called to say it was going to be published. Back in London, I had lunch with the editor who'd bought it. Before we went out, he organised a champagne welcome in the company builidng on Fulham Palace Road.

That's when I knew I was back, I guess. A writer of fiction again. Centre of attention in a communal space between offices.

I'd put on some gladrags for the occasion. By my standards, I was slim, fit, and strong at the time. I had a new girlfriend who became my wife, and they say I'd aged alright for someone in his late forties. The atrium had a couple of sofas and chairs and several bottles of fizz. Eight people, including the editor, his assistant editors, and people from the rights department. Six of the eight were women. Then two more men came down, the guys who were publishing the latest edition of my World Cup book.

Bet you didn't expect this, I said.

Oh I don't know, one of them goes. We knew something like this was in you.

Lunch was good too, at a veggie restaurant near Riverside Studios. Great days - and not just that one.

When Pork had just come out in America, I remember walking through central London one day, near Piccadilly Circus, and feeling like I owned the place. The whole town belonged to me. It sort of did anyway, because I was young - but even more so that day. Same when the first novel came out afterwards. That made me a real writer, I thought. So did Robin, best mate and useful audience.

Twenty years later, did I get that feeling back? London was all mine again?

Well, yeh. Well, sort of. It's complicated.

In those twenty years, I'd occasionally imagine what it might feel like to be published again. When it happened, letdown isn't the word - but I didn't jump for joy like I thought I might. I celebrated with Martin in Italy and my new girlfriend back here, but can't remember how!

For all those years and more, I lived in a two-room flat in Shepherd's Bush. The phone was on the floor beside my bed. And I pictured myself kneeling when the good news came in, then punching the duvet.

I did have a moment like that, but not a huge one and not for a while. At the time, I was very pleased of course, but there was a bit of 'oh well that's alright then'. Maybe I'd been waiting too long.

So I can't quite say the comeback novel gave me back the town (I've never defined myself by published fiction) - it's more that it added to that feeling, which I already had. And that sense of owning London is never going to leave.

I say that even though I haven't had anything published since, despite two attempts. A novel about poker and stamp collecting (well I'd done birds) which publishers rated but couldn't take on because it was about men and men books don't sell (it's mainly women who buy novels).

Then something set in Paraguay, where I spent ten days researching it. I'm still surprised no-one's been interested. So was one of the country's top agents, who took it on ('They don't realise how good this is.'). Oh well, maybe when I'm gone.

In the meantime, I stroll through London like I've been there done that, the sights I've known for years. Everyone else is just doing what I've done before, so you feel - what? A bit superior? Call it happy for people to look at you, quite different from when I first came to London.

In a way, even moving through town is a performance. Check out the chapter on showing off. I don't mean reacting to what's in your earphones (everyone does that) - and I'm not mad enough to sing along.

No, it's the way you walk or just look around, hitch your shoulder bag or wrap a sweatshirt round your waist. I hardly ever think about it, but you're definitely acting a part, and I was always up for that.

What's the feeling exactly? Let's call it papal! I had it ever since the first novel came out, plumped up by the last one.

I called it Pelican Blood. Birdwatching and sacrifice. It came out in two editions over here, and got translated into other languages. This one was turned into a film! Another big advance.

In a spooky full circle, the year the book was launched, Colin Watson died falling out of a tree! No-one shot him, but he was trying to raid a nest. You couldn't invent that.

*

Incidentally, every novel and short story I've written, published or not, has been all my own work.

That's what fiction is to me. Something you think of for yourself.

I can't understand writing a novel based on someone else's. Or putting historical characters together and calling it literature. I could never have written a period drama.

As a novelist, I was a kind of Roxy Music. I know how that sounds, but I came out of nowhere, the opposite of a covers band. Nothing I've ever written has its roots in fiction.

That's partly ego. But I've always believed writers should march to their own drum, or else why bother? I genuinely don't understand adapting novels for films. Write an original script every time.

Do your own thing and nobody else's. Even if the idea seems bonkers.

I mean, who starts with a book of short stories about animals? Why would anyone ever publish that? Then something about a society where age is the only criterion. Then birdwatching and murder; a man breeding dogs in the thorn scrub of Paraguay; London populated by clowns (don't ask); baboons trekking across a world destroyed by climate change (do).

One of the write-ups for the birding book appeared in the lads mag FHM. At the end of each book review, they used to add a box titled 'Who's he ripped off?' In my case, they reckoned, 'Nobody - a true one-off.' Everything that's ever written should pass that test.

Otherwise tell me what's the fucking point.

*

One of the highlights of being published again was the return of Jerry Bauer. One of the highest lights.

Jerry Bauer was a famous photographer. But he wasn't my first.

Back in 1980, when the book of short stories was being out together, the publishers asked me to send them a photo of me, for the inside of the back cover.

But they were in America, where I imagine most people owned a camera. I didn't, same as a lot of people over here. And if the publishers weren't going to pay for professional snapshots, no way was I.

But the answer wasn't far away. Someone who took pictures for a living, with the added value of not charging me anything.

When I started work as a copywriter, the advertising agency was one of the biggest in the world. The London office alone employed 900 people, including an entire food department for testing new products, a department running a cinema complex for showing adverts - and a full-time photographer.

I don't mean to be rude when I say Eric Archer was something of a background figure, with a personality to match. A mild friendly man in his sixties. Ready smile under a scrubby grey moustache. Everyone liked Eric - and he was good at what he did.

He took photos of account directors for prospectuses; creative teams and control departments; leaving parties for bigwigs; people in offices generally. When I approached him, I knew he'd be courteous. A relief that he was keen.

When the first edition of the book came out, I gave him a copy. On the back flap, a potted biog of me, with a photo. In the top right-hand corner of that close-up, the name Eric Archer in capital letters, upside down and going upwards.

My editor hadn't wanted to use that shot. 'I don't think you should look forest-like.' I presumed she meant a bit feral - but I thought that was exactly what they did need: a face to match the 'talented and faintly menacing young writer' in a review by the Boston Globe. And they had to use the photo in the end. Eric had tried a few other head shots, but this was the best.

He was visibly thrilled with the copy of the book. A photographer who took corporate pictures, about to retire, and his name's on a work of fiction. He was actually grateful, when it should've been the other way round.

I was 25 at the time, and at that age I tended to think of myself most of the time. Giving Eric a copy of the book seemed enough to me. But a few weeks later, a lightbulb went on over my head. Maybe I grew up suddenly.

Eric Archer was a professional photographer. And when professional photographers have a photo printed in a book, they get paid for it. That's what makes them professionals.

Eric Archer hadn't been paid. And it finally occurred to me that a single miserable copy of a book wasn't nearly enough. In fact it looked like a sop, like I was taking the piss. It's usually publishers who hire photographers, but I went into Eric's office one day and handed over seventy pounds, with my grateful thanks and abject apologies for being late with the fee. In 1980, seventy quid, for a few minutes' work, was a fair sum. Cash in hand and therefore tax free!

Being the kind of guy he was, Eric said I really shouldn't have. But I really should. And I was relieved that I did, because he died only a few years later, I think just after I left. He was a sweet man, a proper pro, and that photo flatters me to hell. I'm glad I did the right thing by him.

*

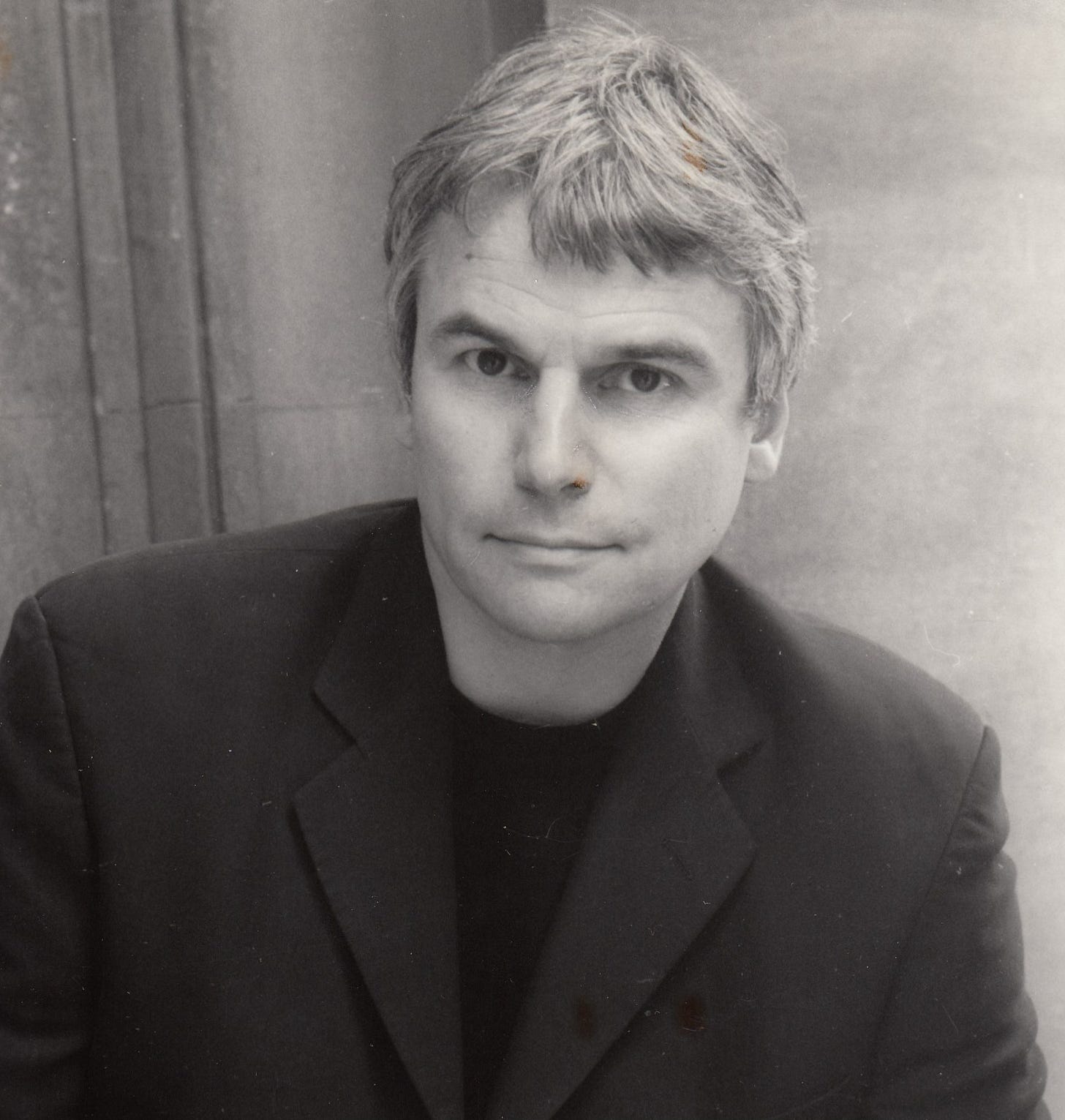

A year or so later, I get a phone call. An american voice, slightly camp, comes on the line.

Is that Cris Freddi?

The same company who'd published my animal stories also bought my first novel. This time they hired a photographer themselves. Quite a privilege to have my picture taken by Jerry Bauer.

He was used by all the major publishers to take shots of their authors, and film studios to snap movie stars. I was in serious company.

He came round to my flat, but I knew he wouldn't think much of it. I imagine most writers lived in houses, with book-lined studies. I had a small white two-room flat in Shepherd's Bush, with hollow doors, a small yard, and cheap bookshelves that bowed! Jerry Bauer was polite. Um, this is OK, but let's do it outside.

So we went to Holland Park, just up the road. I brought the only two jackets I owned, and he took a number of pictures in the archway leading from the ice-cream shop to the orangery. They came out well, I think, though I look more smug than I felt.

That's when I found myself on the end of a trick of the trade, a real eye-opener.

When Jerry Bauer met Elizabeth Taylor, he shot from angles that hid her double chin. One of the authors he photographed was very old, with folds of skin under his neck. I didn't like that, said Jerry. I took it out! He did something similar with me.

I didn't think I had anything a photographer would want to remove. But Jerry did. When he sent me prints, I saw he'd used a white pencil to take out a thin crease across my neck, the hint of a frown line, and some of the character in my face. Makes you look a bit younger maybe, but I was 29!

The celebrities he'd photographed included Pete Townshend. Jerry called him Peter.

Oh, you did him? Striking looks. That nose.

Nose? Can't say I noticed that.

(Ay? It's in your face.)

I said I was a fan of Townshend's music. Saw him on stage.

Music? You saw Peter play music live?

I couldn't understand why he found that unusual - until I eventually realised we were talking about different Peter Townshends! I meant the guitarist with the Who, he was talking about Peter Townsend the RAF pilot who had a liaison with Princess Margaret. A wartime squadron leader of some repute but unremarkable nose.

I didn't see Jerry Bauer for another twenty years. Then I had another novel published.

Is that Cris Freddi?

Then the tone of voice turned arch as well as camp. You're not still living there, are you...?

The shoot took place outside again! Backstreets around Tottenham Court Road. Don't know how much white pencil he used this time, but I'm happy with the result.

For someone who wanted to make you look good, Jerry Bauer was the opposite with himself. I've never known anyone care so little about their appearance.

He'd just turned 70 (though he looked younger), his hair was thinning, and he obviously dyed it, because it was jet black, straggling across his pate like offcuts from Medusa. Short man in a shapeless anorak. I imagine he stood out in Rome, where he lived.

But who cares about all that? He was an expert at what he did, quite a character, and easy company. I'm pleased as fuck to have been photographed by him, let alone twice.

Well known though Jerry was, there's nothing about him on the internet. When he died in 2010, no obits. And nothing about him since. No photographs of the great photographer.

Like my first agent Jimmy Fraser, another giant at what he did, it's as if he never existed. A criminal shame, and I don't get it.

There ought to be something about Eric Archer too.

*

So I had some success writing fiction. So why did I hate doing it?

Well, let me make a musical analogy (I was in a band, remember). Sports writing is like playing the piano. The notes are already there. Same with a rock band memoir.

Whereas fiction's a violin. You have to find the notes yourself. No frets to guide you, so you need to know where to put your fingers. In writing, using my fingers was too much of an effort.

That's why the only prize I ever won was for non-fiction.

I became a birder in 1988, a few months before the Milkins band played its last gig. In March 1991, I spent a few hours on a gorse-covered hillside in Surrey looking for a species of bird I hadn't seen before, and finding two.

Three years later, my girlfriend at the time saw an advert for a writing competition in the BBC's Wildlife magazine. You should enter that.

With what? I thought. That kind of thing, you've got to have an environmental message or some such. All I did was watch birds for fun.

But that day in 1991 was spent on a heath, a landscape that's always under threat. So in the piece I wrote, I included the line 'believing just for today that the heathlands were going to be preserved', then sent it in.

It won.

I took the girlfriend to the awards ceremony in Bristol. Posh dinner and a couple of nights in a good hotel. Applause and photographs. It helped that one of the judges was Chris Packham, who likes his birds.

I got a thousand quid, a pound per word, a serious sum at the time for someone on a low income. They also gave me a certificate and a smart trophy, a wooden carving of a bee-eater on a lump of bark, with a little plaque engraved with my name. Naturally it's in my study to this day. The certificate's in a frame.

As a boy, one of my christmas presents was the 1965 edition of the Guinness Book of Records. Someone knew that's the kind of kid I was, because I devoured it, especially the athletics section. Elsewhere in it, I read that the youngest winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature was 41 at the time. To a ten-year-old, that was ancient (my mum was younger when she died). I was sure I'd beat it one day. Perfectly normal if you ask me: Robin thought he'd be a film director before he was 25.

But I'm happy with my carving of a bird. Though it's a bastard to dust.

*

Just in passing, nobody mentions my writing. No-one ever. And it baffles me a bit.

When I was a teenager, and after that, in the back of my mind I assumed people would find it interesting if you earned your living from writing fiction. I mean, how many novelists do you bump into?

I thought it would be like meeting a guitarist in a band. Or an actor. A painter and sculptor. Makes a change from banker and systems analyst, no?

No.

I had my first book published when I was 26. In the forty-plus years since then, not one person has asked me about it. Apart from Robin, who listened while I read lines out, no-one's asked anything except the odd perfunctory question, and only very rarely.

What's it like having that first copy in your hands? Where do you get your ideas? Not even: what's the book about?

Why? Don't know. Something to do with me personally? When I go to parties and drinks parties, I sometimes think I've got a post-it note across my forehead. 'Uninteresting cunt. Don't bother asking him stuff.' And they don't. About anything.

But that's probably true of everybody. The vast majority of people show no interest in anyone else. I sometimes say I'm the least persuasive person I've ever known. But then everybody is. And I'm marmite. But same again.

People will talk about themselves, though. Oh shit yeh. I ask what they do, how they met their partners, and off they fucking go.

Case in point. I met a violinist once. Pleasant guy from Vienna. Asked him about playing the violin. Couple of follow-up questions were enough for him to talk about it for half an hour. Then the party broke up. As I turn to leave, he finally asks what I do.

I usually tell people I'm a sportswriter. But I didn't think he'd be interested in that, so I said I wrote novels. I'd just had another one published.

Oh, he said. Well -

I held my hands up. Too late!

I kept it light-hearted, but this is what I've had to live with.

If it's not just about me, or not just that people don't give a shit about other people, maybe it's the job itself. No-one's interested in a writer.

They're not on TV talk shows. Literary award ceremonies aren't shown on air. Most novelists, no-one knows what they look like.

There's a lot of books out there, but how many sell many copies? People just don't read.

Probably be different if I earned my living with a rock band. Or acted in a soap, or did stand-up. Played the violin! But in all these years, hardly any questions about my writing. Even from friends of mine.

My last book was about birding. Only a few of my birding pals read it - one of them after three years! 'The time just wasn't right' Wot?

Me, I'll listen to insurance brokers, and policemen and computer programmers and househusbands. And I'm interested. Maybe because I'm a writer. But I wouldn't mind the odd enquiry in reply. Fair exchange, for fucksake.

That's why I stopped going to drinks parties. The post-it note on your forehead: it's put there by the people you meet.

*

There again...

Maybe - possibly - I ask people about themselves because the alternative is me doing more talking - and that involves anecdotes.

I'm not going to say something pompous like 'I'm a natural storyteller', but the urge to tell a tale has always been there. Writing is performing. Telling a story is showing off (see the chapter on that) - and in social situations you have to keep that to a limit. Writing a book, or painting a picture, you can say everything you want, and your audience has to listen.

*

The novels I wrote. I've called them my albums.

But it was films mainly.

I'd be in a cinema (I never thought this at home), and I'd think if I ever had another novel published it would somehow make me a part of that world again. Sometimes if the film had music in it, like The Full Monty. It didn't happen often, which was good because it was too wistful for comfort.

Films, not music. I never thought writing was a kind of rock 'n roll. Fiction came first.

I was born without a voice but a knack for putting words together, so writing a novel was much more important than pop music. It was longer than three minutes, and I grew up with books. Way bigger than rock 'n roll.

Bigger than film stars, too.

I've never understood why they get all the glory when they can't function without the written word. They'll all tell you they take on jobs if they like the script.

Actors can do astonishing things. My wife's an actor, and I marvel sometimes. Different voices in audiobooks, slightest facial expressions. But they all need what's on the page.

Playwrights get acclaim, and film directors. But directors are just conductors, reading from notes. Meanwhile their scriptwriters don't get the glory. Start a campaign. Write in.

*

I'm thrilled to have been in a band, even at the level we're talking about. But the Atrocious Milkins was never meant to last long and I've never missed it. It wasn't what I do.

Writing suits me. Writing on your own.

Not because I'm a loner of some sort. As a copywriter in an advertising company, I worked with two different art directors, and we socialised outside office hours. I was mates with one of them for several years. When I helped set up a major cricket website, I was offered a job full-time partly because I got on with the rest of the team, most of them twenty years younger than me.

No, it's this. Ideas came into my head. For stories. And I didn't want anyone else writing them up. They couldn't have described what was in my mind's eye.

Plus I don't like compromising when I work. Let's put that less pompously: I hate committees. Had to deal with too many in the advertising days - and when I worked for FIFA, eight of us spent all day in the same room and came up with fuck-all. Then we went away, people thought of things on their own, phoned them in, and result.

Proof that you need to be alone to write. You're your own committee, but this one functions.

Having said all that, human beings need both. Time to ourselves but contact with others, a group of you making a thing work. And our thing was a rock band. I was in a rock band. It's a helluva thing to say you did.

You don't write a novel in pairs. But working on a song is different. You might develop your individual parts by yourselves - but after that, you get together and work on the song as a group. Five of you can do that in the same room, whereas comedy writers work in pairs at most (I tried that too).

Learning other people's songs was a serious buzz. Fascinating to break down something you'd already heard, then reproduce it best you can.

But I got more from our donkey track, trivial though it was, because it came from us. We put it together together, everyone bringing something to the table.

Same thing with stage plays at school. I wrote two of them on my own - like the lyrics to our song - then directed and acted with a dozen other people. Best of both worlds.

Performing on stage was something I always liked but could never have done alone. In the band, the five of us were a shield wall that broke out. We covered each other's backs against audiences who weren't interested (there were a number of those) and revelled in crowds who liked to dance to us (there were a number of those). The buzz - fuck it, the joy - of succeeding together. And I don't care if it's irritating when I repeat it: that success was a ROCK BAND.

It gave us a hinterland.

If I hadn't put the group together, I wouldn't have socialised with Harry Hatfield or even talked to Pat Slade, let alone knock about with them for decades afterwards. Being in a band turned my friendship with Bernie Cook into a bond that survived a thirty-year gap.

So although writing, on your own, comes with its own kind of satisfaction, it can never leave the same sort of ripples. That one year at Oxford, man. Still casts a glow over us.

Mixed metaphors are fine. Trust me, I'm a writer.Chapter 58. heroine addiction