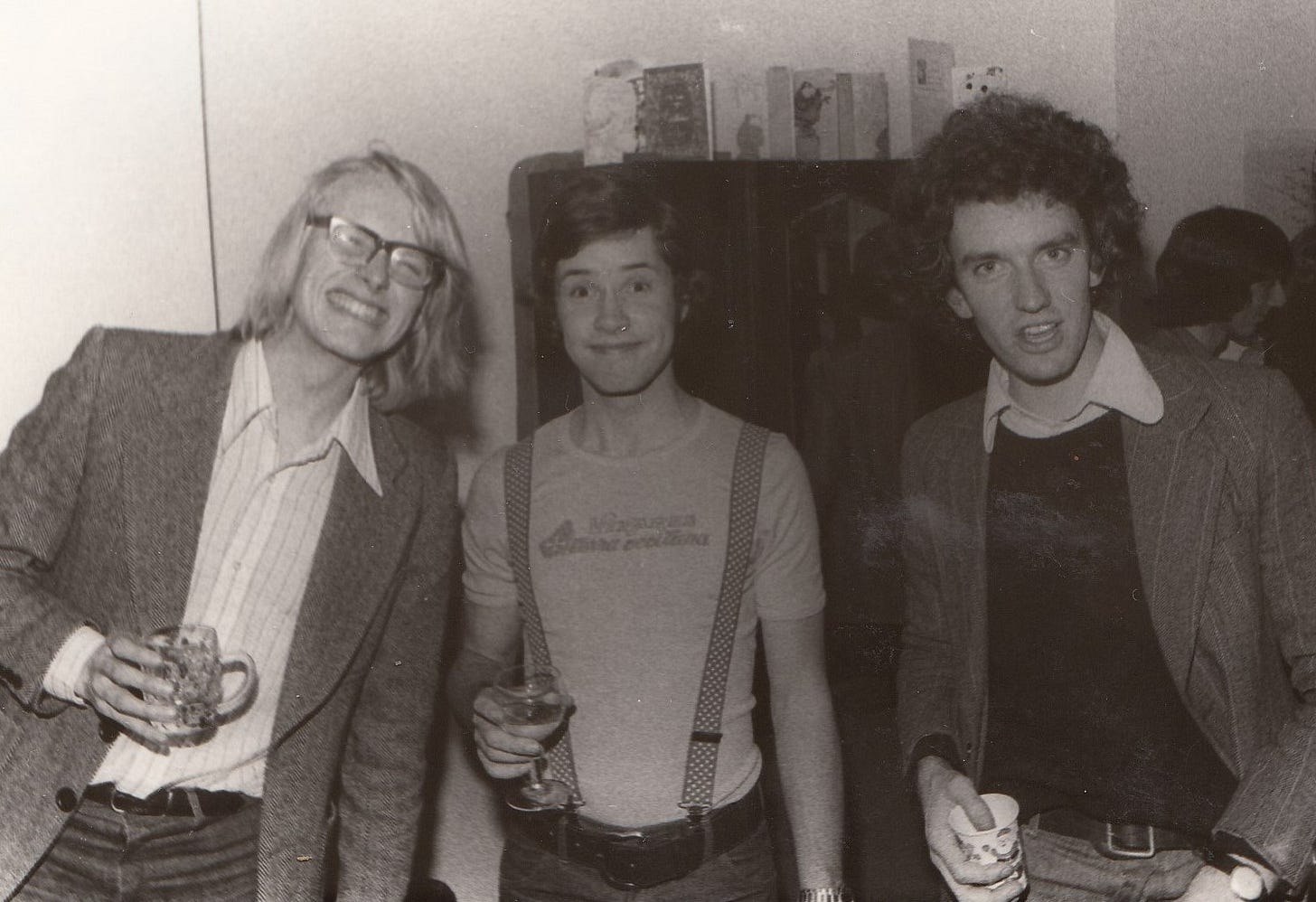

28. the third man

So we'd come full circle.

Back to playing for someone's friends. Apart from a mental hospital, we hadn't really cut it with anyone else.

But this is me looking back. At the time, there was no disappointment, let alone any thought of packing it in. We'd never had any ambitions in the first place. Anyway, some of us were busy revising. Pat and Harry and Blond Steve busier than me, but we were all doing it. You can't really busk Oxford Finals.

*

In between the letter saying I'd been accepted at university (December 1972) and actually going there (October the following year), I worked at the hospital as always. In the staff canteen, I'd sometimes sit at a table with two male nurses, a few years older than me. One of them, Phil Newport, a lovely man with a stutter, worked on the ward I cleaned.

They both had long hair and beards, and they were in a band. They named it Gull, the usual prog rock or something similar. They played at the hospital's social club once, where they were a tad loud for the middle-aged members.

The other guy, not Phil Newport, had been to Oxford. He didn't give me any pointers about life as a student there, but did say something about the exams at the end .

People tell you, he said, that Oxford finals are the toughest thing you'll ever go through. Thirty hours of hell. But they're not that bad. Students can do exams.

By the time they came round for me, I felt the same. You do those thirty hours ninety minutes at a time.

Saying that, I knew I wouldn't do well. I'd gone in for some late revision, but hadn't put in the hours over the years. The enjoyment, such as it ever was, diappeared before I arrived. And I knew how it was all going to end even before I walked out of the Dante exam forty minutes early!

If you did italian at university, you had to do the Divine Comedy. Maybe you still do. The first major work in the tuscan dialect, which became the italian language. All very seminal - but most of it utter shit.

Inferno is alright, just about. Cruel as fuck, but we all enjoy villains from history. But Purgatorio is precisely that, a boring slog, and Paradiso simply fucking unreadable (his beloved Beatrice is just so dull). If more people had written books in those days, most of them wouldn't be highly rated today. We moved on a long time ago.

That attitude wasn't going to get me far in exams. I knew I hadn't passed the Dante and others, though I must've done alright in one or two because I didn't fail outright.

But Oxford wasn't going to let me off that lightly. I'd taken other penal tests: the essay after coming back early from Rome, the remedial chats. Now they hit me one last time. A viva, short for viva voce, live voice. An oral examination, to see if I really knew what I'd been writing about. Uh-oh.

I tried to get out of it. I phoned Keith, my tutor at Worcester, and asked if I could just accept the lower class of degree and not have to turn up. I knew I wouldn't pass the orals, and I was happy with a third.

Well, he said, you could...

But there are two problems with that. First, if you don't turn up for an exam, it's a breach of etiquette, and they have the right to mark you down for it.

(Fine by me)

Secondly - and I'm sure this isn't the case - it could be between a third-class degree...and no degree at all...

(Oh fuck)

I agreed that I hadn't done so badly they'd let me leave with nothing. But I guess you never know, so I went along to the exam schools on the High Street, where I'd taken an oral exam before. I'd passed that one, but this time I was ready for ritual humiliation.

Someone else from the Worcester language set was there too.

Steve Crawshaw went on to work for Human Rights Watch, Amnesty, and Freedom from Torture. I didn't socialise with him at college, but he was a friendly guy, with a good sense of humour. We met up a couple of times in London. His favourite word in english was 'fiend'. I haven't thought of a better one. The worst is 'ablutions'. Or maybe 'butterfly'.

He was involved in staging plays at Worcester, and he was obviously good at the course work, because his viva today was for a first or a second, the opposite end from me.

He got the first. If anyone achieved that from our group, I'm glad it was him. Some of the others wanted it too much. One of them (who once claimed he was better than the rest of us!) even went to the Radcliffe Hospital for sleeping pills. They sent him home.

As for me and the viva, best I can say is that it started surprisingly well.

I'm wearing the usual scruff, but you have to put a gown over it. Like last time, I'm sitting facing a table with half a dozen examiners looking back at me. Go on then, guys, let's get this over with.

They ask me a question.

Your essay on ambiguity in Molière.

Yes.

You mention ambiguity of punctuation.

That's right.

Could you give us an example of this?

I could. The only writers I got into at all were the playwrights. Not Beckett but Ionesco with his chairs and rhinos and murder by a professor! Good college fare.

And I'd liked Molière at school. Satire with a scalpel, spare stage directions that give directors more freedom. He led to my first curry, too.

But ambiguity of punctuation, I see you frown. Really?

Oh yeh. And I amplified.

In Tartuffe, there's a scene where the wife's sitting with the religious hypocrite, and the husband's under the sofa, persuaded to eavesdrop because she wants him to hear what a slimeball the faux devot is.

The Tartuffe refers to the husband as 'a man, between you and me, to lead by the nose'. In one manuscript, the comma's missing after 'a man', which makes 'between you and me' physical as well as figurative: it refers to the husband between them under the couch. Get that?

The examiners did. They were visibly impressed. So was I. This might not be so bad after all -

Good, says the first guy. Now, moving on from Molière.

(Uh oh)

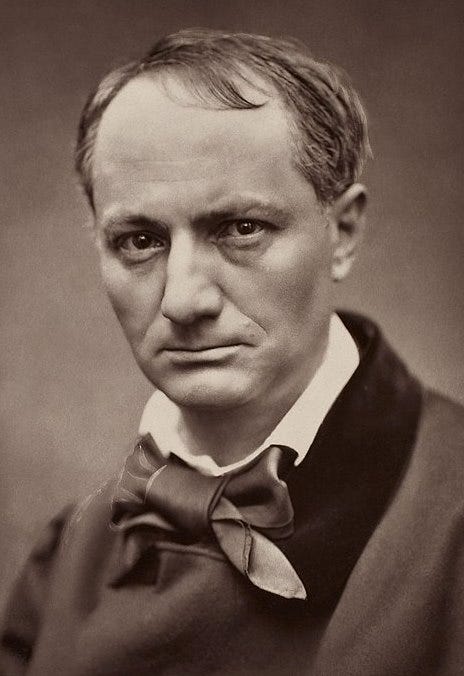

They moved on to Baudelaire. And I knew I wasn't getting out of that alive. There's well over a hundred poems - and I can't remember reading any at all!

The guy asked me about the first one.

Ah yes, I said breezily. Au lecteur. To the reader.

Er, no. Not the introduction. The first poem in the actual collection.

I didn't know what it was! Still don't, and I ain't lookin' it up. The only bit I remembered from the entire collection was the very last line of the intro: Mon semblable, mon frère (hypocrite reader, my likeness, my brother).

Imagine that. A famous poet, a well-known drug taker, therefore quite rock 'n roll - and here's a final-year student, at an elite university, writing an essay on him without reading the fucking text. Not even the opening poem!

What possessed me to think I could get away with it? Why choose that for an essay? Maybe I decided poems were easier than novels. I was at Oxford, for christsake. Never mind a third-class degree: I deserved a tenth.

The viva didn't get any better, but at least it didn't last much longer. They asked another four questions, about different writers, and I couldn't answer any of them. Nope, sorry, got me again.

In the end, the foreman says 'I don't think we need detain you any longer, Mr Freddi'! We all smiled as I left.

*

I got a third, of course.

Quite right too, with the amount of work I'd done for it - though I have to say my two tutors throught I had potential for much higher things if I'd been more interested: Messrs Gore at Worcester and Robey in Magdalen. Over a glass of Punt e Mes, David Robey told me how astounded he was, and 'rather depressed', that I'd never been up for it. He was the opposite, of course, steeped in italian studies.

Meanwhile I've been perfectly happy to announce my third over the years. Others haven't.

I can think of four others who got the same class of degree. None of them mentioned it before I did.

Two of them were at the same table as me. It's 2001, I've joined a team setting up a major cricket website, and three of us are in the canteen. One edits the site, the other became the editor of a major cricket mag. The first one, not the magazine editor, he went to Oxford like me, several years later. Said he regretted his third.

So did a girl I met, friend of a friend. She'd been to Cambridge. Now she was studying for a retake, hoping to do better.

If I'd got a third without being in a band, it would've summed up my last two years at college.

*

I found out about my degree by phone, which was rare in those days, certainly within Oxford University.

As I say, to get in touch with someone in a different college, you either went round there in person (it's a small town) or you dropped a letter in a pigeonhole and it was posted for free. You never phoned anyone. No mobiles, of course, and no landlines in college rooms or most rented houses, including ours.

Someone who did have one was one of the Worcester language class. Though why I'd be calling him, I don't know. He was the one who laughed when I lost a girlfriend at the end of year one. The piss-taker Steve kicked when he was down.

He lived in a house with his wife. I'm on the phone to him about something, and he mentions the exam results have come in. Oh I'm sorry, Cris, you've got a third. If you didn't know him, you'd think he was genuinely commiserating. But I could feel his glee from here.

You didn't get a 2:1 or a 2:2 at Oxford, just grade 2. So I came within an oral exam of having the same grade as him...

...after spending the last three terms in a rock band which finished the year in style and led to girlfriends I liked. Meanwhile he slept apart from his wife to keep himself fresh for his attempt at a first! He got a second. I know which one of us was happier with our result.

Many years later, I had dinner with this guy in London. Fuck knows why, because I knew he'd never liked me. So I was on best behaviour all night. Then one wrong word at the end and he gives me grief, like he'd been waiting for it. Total tosser.

*

When I came out of my last finals exam, one of the Worcester language set ran off to buy a bottle of champagne, but I didn't feel that way at all. Anyway, I had family there to meet me.

My dad, maybe my brother and his girlfriend, and definitely my uncle. Dad's brother Guido was a real surprise, because he didn't come over from Italy much. We went to a pub before lunch somewhere else. At one point, I ask him something, in italian of course, and he leans over and says don't speak in english, Cristiano, I can't hear so well! Christ, no wonder I had to retake my italian oral.

Actually, it worried me a bit, because he was obviously going a bit deaf, like my dad. It was the last time I saw Guido, and it hurts to think about him. Bear with me.

*

hearing loss

I don't know how many brothers my dad had. His parents produced mainly girls. He was the youngest of 13 or 14 (my grandad had two or three others from his first marriage!) - and I don't know the names of four or five of them. You'd think there must've been one or two boys among those, but I knew only one of them. So did my dad. By the time he was born, only six of his siblings had survived infancy, including just one brother.

My grandparents on that side died early, so Guido and my dad were sent to an orphanage, though not at the same time. Grim places in those days, no better than prisons. The various aunts who now looked after Dad's family couldn't afford to feed all of them, so Guido was sent to the orphanage. But other kids treated him so badly the aunts genuinely feared for his life, so they took him out and sent my dad in. That's what those places were like. My dad knew, because he'd been in one. And he still sent me to boarding school.

Photos don't do Zio Guido justice. Very good looking, especially as he got older and filled out a bit, changing from a character actor specialising in 1940s mobsters to a leading man! I can still hear that deep voice of his.

It was something my dad missed when Guido killed himself.

*

Like so many of that family, he'd had a hard life. The orphanage that put him in danger, hard work for little pay - and an unhappy marriage.

I liked Zia Mariella when I was a little kid. She was always lively. But I remember thinking she wasn't good looking enough for Guido! The poor woman was bi-polar and couldn't have kids, so their life together was difficult. Especially when he started to lose his hearing.

There used to be a giant sugar factory in Casalmaggiore, the zuccherificio, so big and important it had its own mini railway. A couple of the buildings are still there and look quite palatial. I was told the noise in that factory was horrendous, and it probably contributed to Guido's deafness.

His mates took to calling him Il Sordo, the deaf man, but I hope they stopped when it wasn't funny any more. He really couldn't hear what they were saying, so he started avoiding company and shrank inside himself. There was talk of another woman, but that didn't go well, and anyway coming up to sixty can be a dangerous time. I knew Ted Moult for a while.

I imagine my uncle looked back at his life, then looked forward and saw nothing but isolation through deafness and an old age with a troubled wife. My cousin Stefano showed me his suicide note. This may sound trite, but it was a privilege to read it. I can't remember any clear reason for what he did, but he asked his wife to forgive him.

My aunt Sandra, who brought me up, told me 'I Freddi sono sfortunati', the Freddis are unfortunate. I look at the generation before me, and mine, and couldn't agree more. Though some of us didn't make our own luck.

They say Zio Guido doted on me when I was there as a toddler. What with having no kids of his own. I remember going back there when I was eight, and him being determined to buy me a pair of shoes. Doesn't sound much - but these were italian shoes. Light brown brogues with stitching. Even at that age, I knew they were special. Expensive, too - but my uncle wanted me to have them. So much so that I agreed - even though they were a size too small! It would've been alright to tell him that, of course, but I didn't want to hurt his feelings. Hurt my feet instead, then couldn't wear them when I got back to England.

In 1998, Stefano took me to the cemetery to see Guido's grave. Much grander than I expected. An almost life-size statue of Michelangelo's Pietà in black metal, with a framed photo of my uncle at its feet. In certain situations, italians still use the formal form of address, with the surname first: Freddi Guido (which looks the right way round to the english).

Wish his life had been a lot happier, because he was a star of the family.